"The Power Only We Possess": Coalition Politics at the 1970 Philadelphia Revolutionary People's Constitutional Convention

The Black Panthers, the Gay Liberation Front, and the Radicalesbians walk into a conference hall...

Hey <3 I’ve been laboring over this essay bit by bit for weeks. Existential despair about the climate, Gaza, and the election have no doubt slowed me down. Nevertheless, it seems to me that learning from the successes and the failures of radical movements past has never been more important, and I’m grateful to get to do this research and to have you alongside me as a reader. This essay is about the process of establishing coalition politics, so I want to give a shout out to this essay by

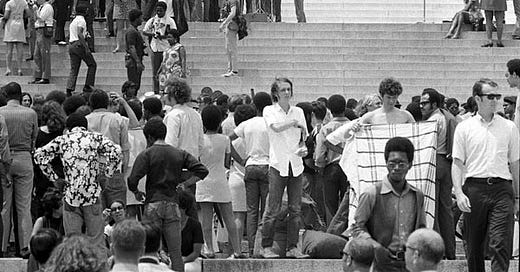

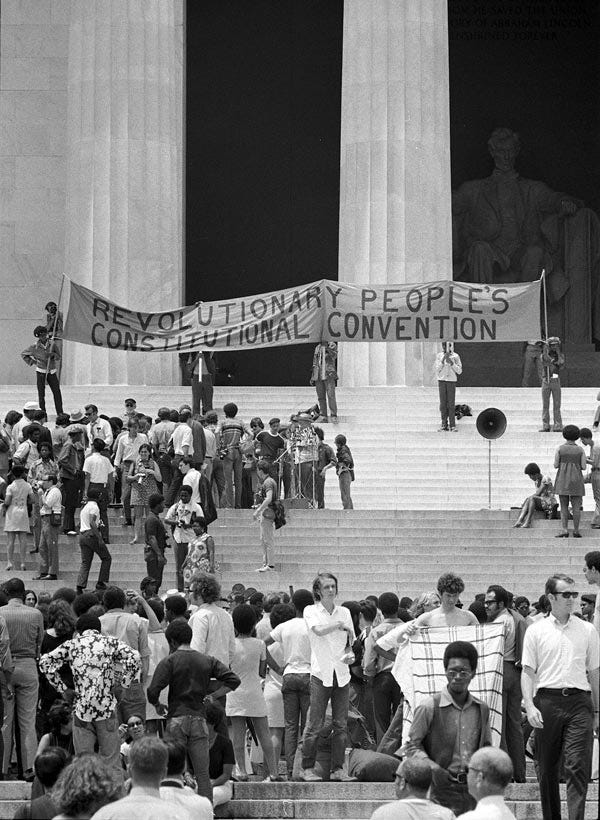

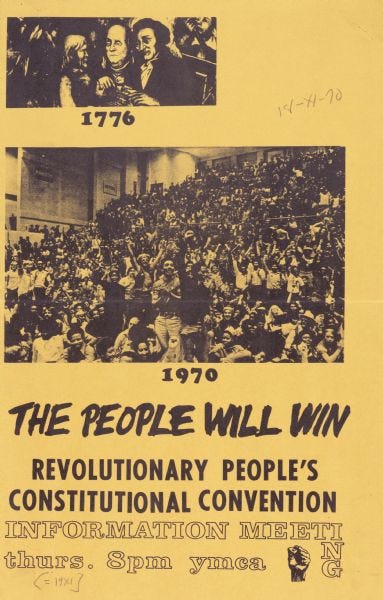

about, among other thing, coalition work in the present moment - one of the only pieces of post-election writing I’ve read that’s really reaching me where I’m at. PS: This post is too long for email, as is my way - if you’re seeing this in your inbox, to read the whole thing click the link to read it in your browser.On June 19th, 1970, the Black Panthers Party took to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. to deliver a message. David Hilliard, the BPP’s Chief of Staff, read a prepared address: “As oppressed people held captive within the confines of the Fascist-Imperialist United States of America,” he began, “we Black Americans take a dim view of the position that we, as a people, find ourselves in at the beginning of the 7th decade of the Twentieth Century.”1 It was the 107th anniversary of the end of chattel slavery in the United States, and yet, Hilliard declared, “Black people still are not free.” Despite the passage of civil rights bills, he went on, “the Constitution of the U.S.A. does not and never has protected our people or guaranteed us those lofty ideals enshrined within it.” It was time for Black people and revolutionary allies to create a new vision for society. He then announced:

WE THEREFORE CALL FOR A REVOLUTIONARY PEOPLE’S CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION, TO BE CONVENED BY THE AMERICAN PEOPLE, TO WRITE A NEW CONSTITUTION THAT WILL GUARANTEE AND DELIVER TO EVERY AMERICAN CITIZEN THE INVIOLABLE HUMAN RIGHT TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS!

This convention, the statement went on, was not just for Black people:

We believe that Black people are not the only group within America that stands in need of a new Constitution. Other oppressed ethnic groups, the youth of America, Women, young men who are slaughtered as cannon fodder in mad avaricious wars of aggression, our neglected elderly people all have an interest in a new Constitution...Only through this means can the present character of America, the purveyor of exploitation, misery, death, and wanton destruction all over the planet earth, be changed.

I am struck, reading these words, by the optimism they contain: a belief that the people coming together to stake out a new Constitution could really change the very character of America. I’m struck, too, by Panthers’ faith, however bruised and tempered, in U.S. historical and governmental forms. Their choice of language, location, and iconography was explicitly tied to the history of the Revolutionary War, the founding fathers, the creation of the original U.S. Constitution. Like the revolutionaries of 1776, too, the Panthers were not afraid to use violence. The final lines of of the announcement read as follows:

It had best be understood, now, that the power we rely upon ultimately, as our only guarantee against Genocide at the hands of the Fascist Majority, is our strategic ability to lay this country in ruins, from the bottom to the top. If forced to resort to this guarantee, we will not hesitate to do so.

FOR THE SALVATION, LIBERATION, AND FREEDOM OF OUR PEOPLE, WE WILL NOT HESITATE TO EITHER KILL OR DIE!

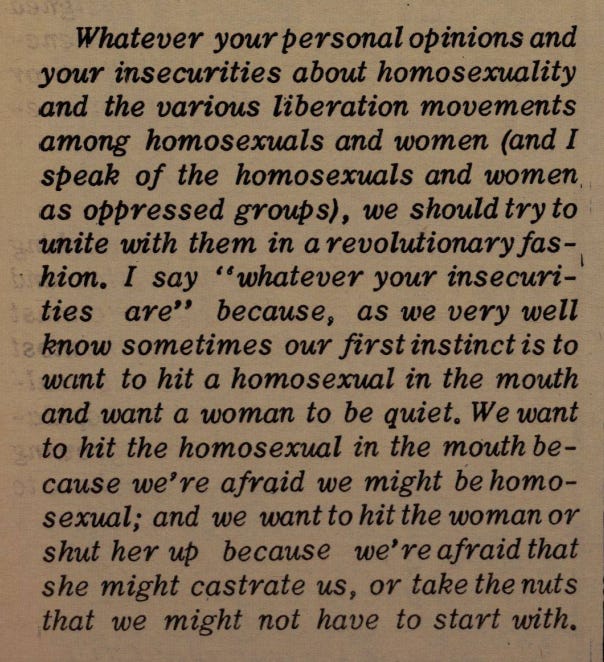

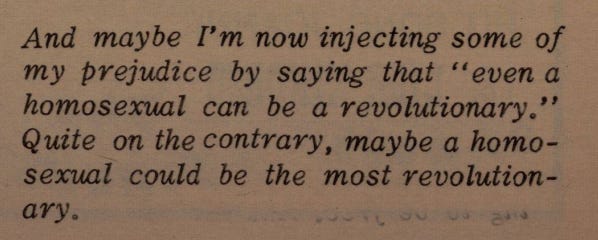

In service of the Panthers’ plans to foster a wide coalition with this convention, the BPP co-founder and leader Huey Newton released another statement that was widely republished in radical rags. Titled “A Letter from Huey Newton About Women’s - And Gay - Liberation,” the letter addressed members of the Black Power movement and called on them to show support for the women’s movement and gay liberation.2 Newton first acknowledged that there had been uncertainty in Black movement spaces about how to relate to the burgeoning women’s and gay liberation movements. He then wrote:

This is a stunning piece of writing in the truest sense; in just a few sentences, Newton seamlessly expresses, owns, and critiques violent impulses against women and gays, implicating both the reader and himself in the process. Ultimately, Newton explained, a new “revolutionary value system” hadn’t yet been fully established, and the process of establishing required recognizing the oppression of others. Though Newton explained that he himself was not entirely comfortable with homosexuality, he fundamentally believed that “a person should have freedom to use his body in whatever way he wants to.” Who knows, maybe even a homosexual could be revolutionary? And then, as though working through his thoughts on the page, Newton wrote this:

Well, damn! Newton went on to encourage his readers to view the women’s and gay liberation movements as potential friends and allies, allowing one another to make mistakes and avoiding using words like “faggot” or denigrating Nixon by calling him gay. “We should try to form a working coalition with the Gay liberation and Women’s liberation groups,” Newton wrote. “ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE!”

This address was galvanizing to a great many people of all races in the gay liberation and feminist movements. Though all three movements both drew on experience from Civil Rights movement organizing in the 1960s, these movements were often quite segmented from one another. Not entirely, it’s worth noting: historian Jared Leighton wrote a fantastic article, available for free online here, about engagement between the Panthers and the gay liberation movement in the Bay Area prior to the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention, rooted in the groups’ shared investment in combatting police violence.

Leighton documents the varied responses of gay liberationists to Newton’s statement. There were skeptics: some who didn’t share Newton’s vision of revolutionary societal overthrow, and others who doubted the depth of the Panthers’ commitment to gay liberation. However, for many, Newton’s statement promised to usher in an exciting new era of collaboration. Lesbians in Berkeley formed a BPP-inspired Women’s Militia. Gay Liberation Front (GLF) chapters across the U.S. issued statements of support for the Panthers. In Detroit, members of the Panthers attended a GLF meeting, and invited the GLF to participate in its Breakfast for Children Program.3 For radical Black and Third World gays, Newton’s statement offered a path toward integration between parts of their lives and politics. In the newspaper Gay Sunshine, a Black gay man named Ron Vernon wrote that the Panthers “[have] begun to relate to homosexuals a[s] people, as a part of the people. That’s when I really became a revolutionary, began to live my whole life as a revolutionary.”4

Radical groups from around the country excitedly prepared to attend the convention. The FBI was also excited. COINTELPRO files released through the Freedom of Information Act reveal that the FBI attempted to sabotage Rutgers students using a university grant (technically public funds) to charter a bus to the convention. Even more absurdly, agents hatched a scheme to sow distrust amongst the convention planners by injecting oranges with laxatives, mailing them to the convention planners as a food donation, and then sending a telegram, posing as a Panther from Oakland, warning that tainted food is hiding amongst the donations. “Confusion, intra-BPP distrust, and hunger at the upcoming convention would be the results,” the memo explains.5 Though it is not clear from the documents whether these plans were put into action, these memos are of a piece with the vast history of FBI sabotage of the Black Panther Party and other Black radical organizations, as well as radical feminist and gay liberation groups.

The city of Philadelphia also attempted to crack down on the Panthers in the lead-up to the convention. The Philadelphia Police Department raided BPP offices across the city just days before the convention was to begin, and arrested five women and ten men. Horrifyingly, the PPD publicly strip-searched some of the Panthers while making arrests and photographed their naked behinds, running pictures of exposed Panther members standing beside armed officers in the paper.6

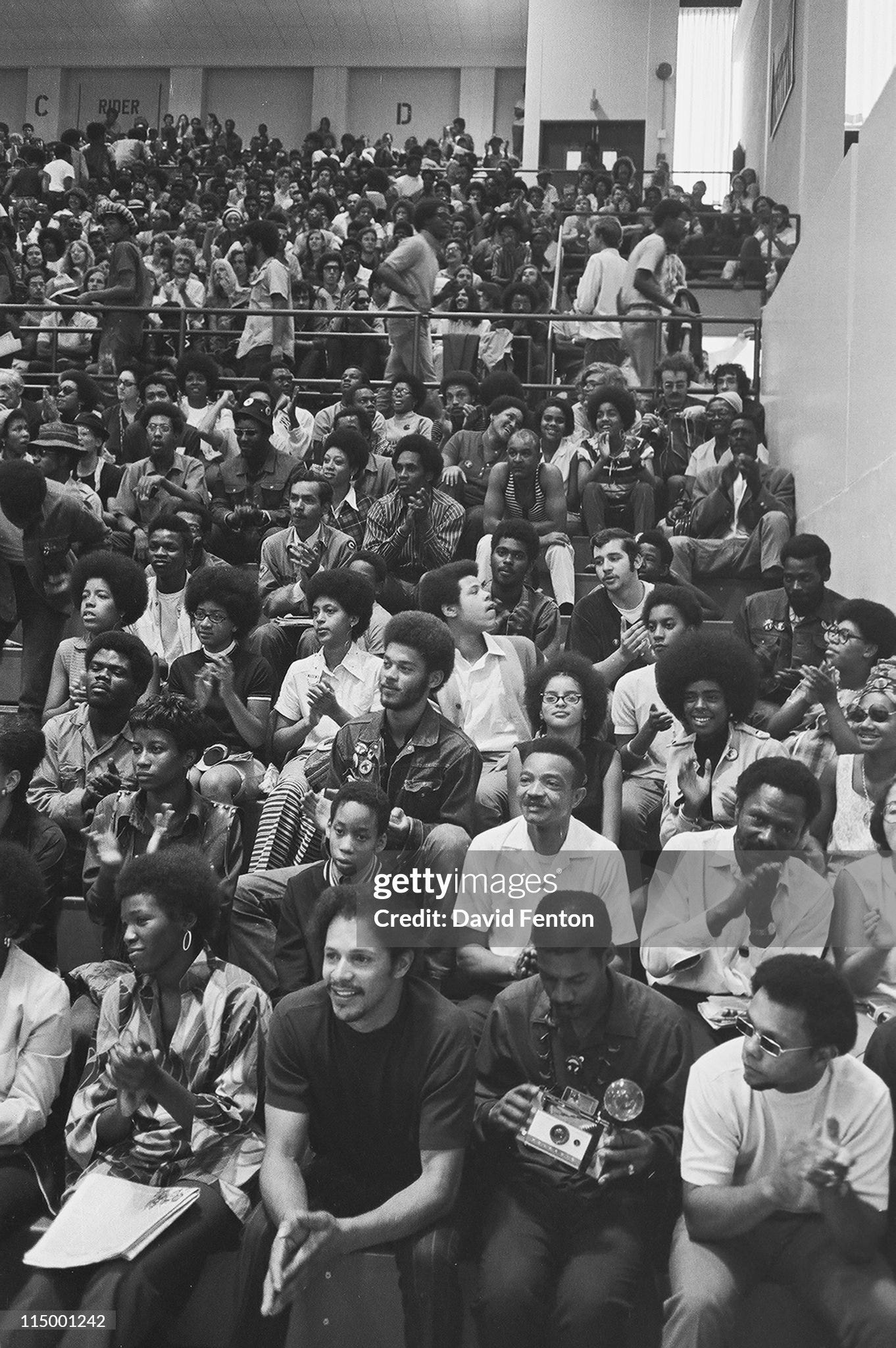

Despite these government sabotage attempts , an estimated ten to fifteen thousand people descended upon Philadelphia for the convention, including members of the Weathermen, the Young Lords, Students for a Democratic Society, the Yippies, the Radicalesbians, the Gay Liberation Front, the American Indian Movement, and more. George Katsiaficas, historian of left movements, was in attendance, and he recalled that he arrived in Philadelphia to find “the streets alive with an erotic solidarity of a high order,” with local Black families and churches opening their doors to welcome convention attendees.7 In front of the convention center hung five flags in descending order: the Panther flag, the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam flag, the black nationalist flag, the Yippie flag (a green pot leaf superimposed on a Marxist-style red star, on a black background), and a flag of Che Guevara.8

The convention’s opening plenary session took place at McGonigle Hall at Temple University, and thousands crowded into the room with many more people waiting outside. As the Gay Liberationists entered the hall, they began to chant and clap: “Gay, gay power to the gay, gay people! Black, Black power to the Black, Black people!” Throughout the hall, Katsiaficas recalls, the crowd rose to their feet, adding other descriptors to the chant: Red people, Brown people, women people, youth people, student people.9

The session featured speeches by Huey Newton, the Black Panthers organizer Michael Tabor (who later permanently fled the US for Algeria after being charged with conspiring to kill police officers), the Massachusetts Black Panthers leader and scholar of African American Studies Audrea Jones Dunham, and the Armenian-American civil rights attorney Charles Garry. Newton spoke last, and his speech was highly anticipated; he had been released from prison just a month earlier after his conviction of voluntary manslaughter for killing a police officer had been overturned, and many people in the room had been involved in the Free Huey movement over the last two years. Katsiaficas recalled that, when Newton finally spoke, the crowd was disappointed; he spoke in a “high-pitched, almost whiney” voice, making “abstract analytic arguments” that failed to galvanize the audience.10 Not everyone shared this assessment; an article about the convention in off our backs noted that Newton delivered an “economic analysis of the role of the Constitution,” and that he “signifies the collective strength and aspirations of the thousands of militant blacks and whites - that he is now walking the streets is a tangible symbol of the power the people are only beginning to realize that we, and only we, possess.”11

The next day, the convention broke into identity-based workshop groups to develop group demands, to be included in the eventual Revolutionary People’s Constitution. The breakdown of the conference into discreet identity groups posed challenges for some: if you were, for example, a Black lesbian college student, would you attend the Third World workshop, the Women’s workshop, the Female Homosexuals workshop, or the College Students workshop? Accounts vary on how these workshops were orchestrated; some accounts complain that the Panthers confusingly canceled workshops at the last minute. I think it is safe to say that the convention was an imperfectly organized massive event with many moving parts, which at times created confusion and chaos. Still, we know for sure that a gay men’s workshop, a women’s workshop, a lesbian workshop, and a Third World gay caucus all met and developed demands.

The Male Homosexual Workshop convened at the Germantown Presbyterian Church, and drew a multiracial crowd with some participants in drag. One workshop attendee reported in an article in the magazine Gay Flames that “we were treated to the vision of two brothers fucking on top of the church’s silk AmeriKKKan flag.”12 Members of the gay workshop picketed two Philly gay bars known for racist practices, met with Afeni Shakur of the Panthers, and completed a statement of demands. On Sunday, their report was shared with the rest of the convention by Philadelphia gay activist Kiyoshi Kuromiya (who I will write a full post about sometime). An article in Come Out reported that, though Kuromiya was initially met with “snickers” when he took the stage, in the end his presentation was “enthusiastically applauded.”13 The report declared that “the revolution will not be complete until all men are free to express their love for one another sexually.”14 Kuromiya later explained that the statement was designed to show how Gay Liberation was not just a struggle for civil rights for a small minority but rather a movement to transform society for all: the struggle to create “a society in which people can come out and be all that it’s possible to be.”15

The lesbian caucus did not go so smoothly. In a collectively-authored article published in off our backs, a self-identified “group of New York Lesbians” (who I believe were the Radicalesbians, though I’m not 100% sure) reported that they had faced constant roadblocks at the convention. The article, titled “lesbian testimony,” explains that the lesbian workshop (along with the other identity-based workshops) was confusingly cancelled last minute, and the Panthers denied the lesbians’ request to announce an alternate meeting time for the women. The lesbians took this denial to mean that “women who dare to identify with their own oppression were felt by the Panthers to be a serious threat.”16

Nonetheless, both a Workshop on the Self-Determination of Women and a Lesbian Workshop managed to convene. The meeting for the Workshop on the Self-Determination of Women, the article writers complain, was “presided over by a Panther woman with male Panther guards ringing the room and balconies.”17 When members of the workshop protested that the male guards were creating an intimidating atmosphere, they were told that they were necessary for the female Panther member’s protection. The lesbian article writers explain that, during the meeting, their ideas for demands “for actions leading to the real equalization of power between the sexes” were “met with charges of racism and bourgeois indulgence” by “male-identified Panther and YAWF [Marxist-Leninist] women.”18 A quick note of translation - “male-identified” does not mean “identifies as a man” here. Rather, it is used, derogatorily, to refer to women who are invested in male-led political and social groups, in contrast to “woman-identified women,” a term created by the Radicalesbians to describe a lesbian ethos in which women’s social, political, and romantic energies were invested as much as possible only in other women. It isn’t hard to imagine that some lesbian members brought their preexisting baggage about participation in male-led groups into the workshop, thus coloring all conflict within the space of the workshop as boiling down to a difference between “male-identified” and “female-identified” orientations.

A particular sticking point emerged around attitudes toward the nuclear family. “Our demand for the abolishment of the nuclear family, heterosexual-role programming, and patriarchy was called bourgeois,” the article notes. Marc Stein, a scholar of LGBT history, observes that “alliances foundered on the question of ‘the family’” frequently in these years, as “straight activists of color tended to identify the family as a source of strength and a foundation for liberation,” while white lesbian feminists and gay liberationists “often pointed to the family as a source of oppression.”19 Stein notes that, at the convention, gay men of color who participated in the Male Homosexual Workshop co-signed that group’s “indictment of the nuclear family,” while the women of color at the Workshop on Self-Determination for Women (none of whom, as far as we know, openly identified as lesbian) supported the lesbians’ calls for family abolition.20 The white lesbians’ inability to understand why, for example, Black women might not be so keen on an agenda that involved surrendering parental custody of children over to communal care, meant that a shared radical vision within the workshop remained out of reach.

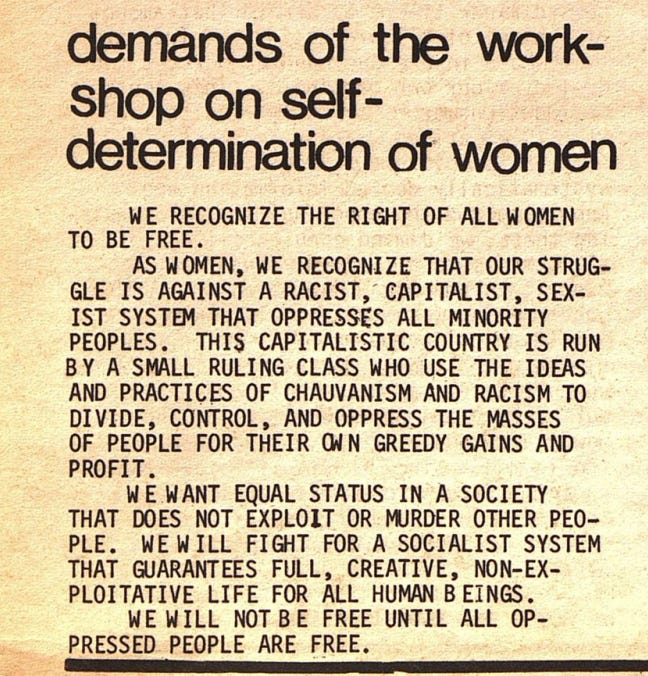

Facing what they saw as insurmountable barriers to collaboration, the New York lesbians decided to bounce. The demands ultimately produced by the workshop (reprinted in oob) began thusly:

The demands then go to list calls for “socialization of housework,” growth of “communal households and communal relationships and other alternative forms to the patriarchal family,” women’s right to determine their own sexual orientation, an end to gendered labor exploitation, educational self-determination for women, equal participation in government, and more.

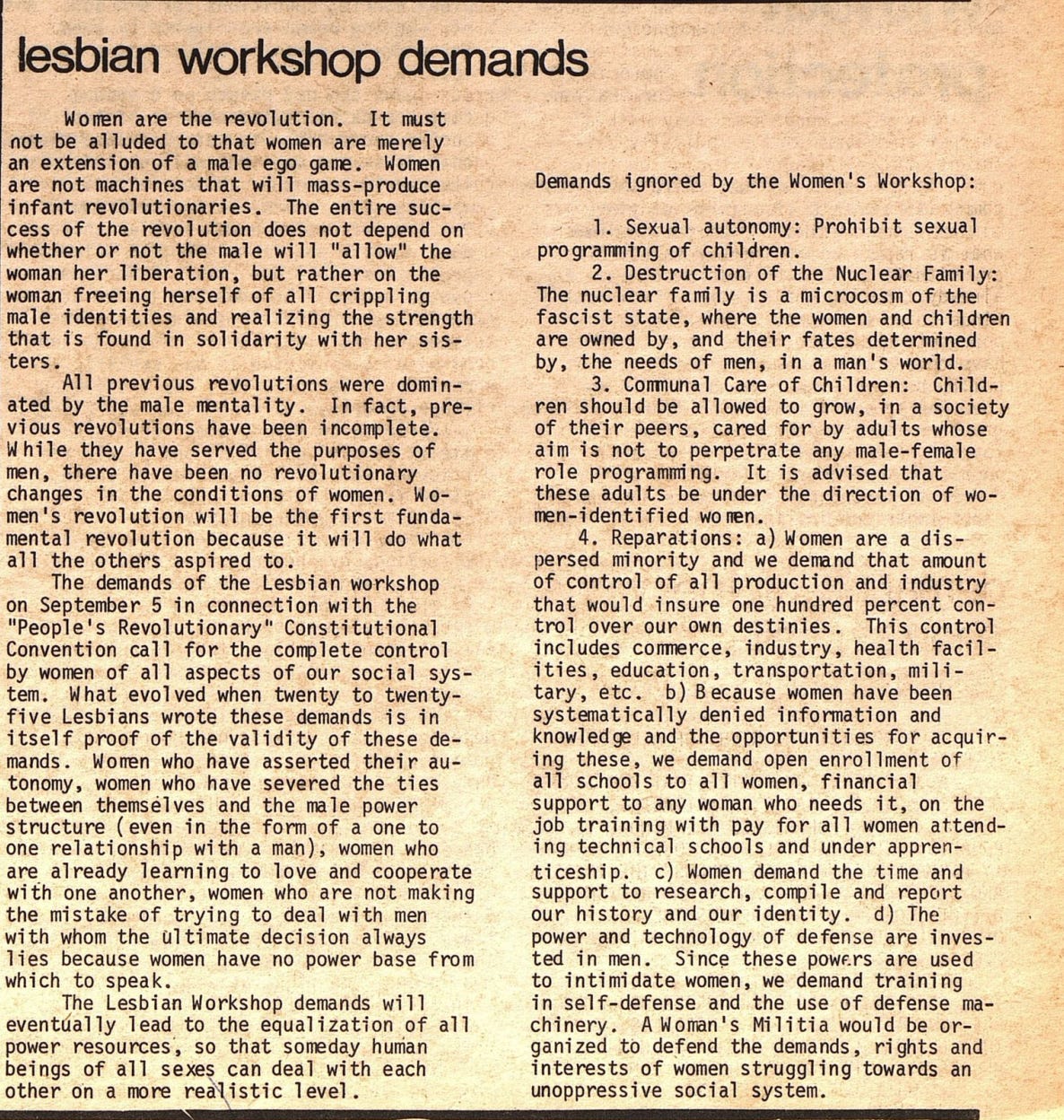

Though these demands read to me as quite radical (and indeed arguably none of them have been achieved at scale within our society), the lesbians produced their own demands, which started with the line “women are the revolution,” and went on to list “demands ignored by the Women’s Workshop.” Their demands are as follows:

Marc Stein argues, I think correctly, that the Lesbian Workshoppers were “making a bid to be the convention’s vanguard.”21 Hence their insistence that it was their revolution that would “do what all the others aspired to,” which reads today as a form of arrogance and misguided belief in the primacy of sex as the root of all oppression. No wonder the Black Panther and Marxist women were turned off by their ideas!

While doing the research for this post, I couldn’t stop thinking about Bernice Johnson Reagon’s canonical speech from a decade later, titled “Coalition Politics: Turning the Century.” Reagon, who was a Black lesbian musician, composer, historian, activist, and founder of the a cappella group Sweet Honey in the Rock, first delivered the essay as a speech at the 1981 West Coast Women’s Music Festival. If you haven’t read “Coalition Politics” before, I highly encourage you to smash the link above and spend some time with this provocative and timely text.

Reagon’s message is basically this: if we want any collective hope of a livable (let alone just) future, we will need to invest in the work of coalition, and that shit is hard. “I feel as if I’m gonna keel over any minute and die,” Reagon said at the festival. “That is often what it feels like if you’re really doing coalition work. Most of the time you feel threatened to the core and if you don’t, you’re not really doing no coalescing.”22 Coalition isn’t about having fun or being comfortable or even liking one another. “You don’t go into coalition because you just like it,” Reagon said. “The only reason you would consider trying to team up with somebody who could possibly kill you is because that’s the only way you can figure you can stay alive.”23 In the face of environmental crisis, the crushing reality of late-stage capitalism, the weight of centuries of racism, ableism, sexism, homophobia, we don’t have to like each other, but we do have to recognize that we need each other.

In her speech, Reagon highlighted the contrast between coalition and separatism. The setting of the speech was relevant: a women’s music festival in 1981 would have contained a lot of lesbians, particularly white lesbians, who were highly engaged in the work of building separatist cultural spaces. Reagon’s speech pointed out the political limitations of this work. Separatist spaces, where you feel comfortable because you are surrounded by others who are basically like you, are spaces for rest and recovery, but, according to Reagon, they are not spaces where real political work is done. “It’s nurturing,” she said of separatism, “but it’s also nationalism.”24 And, though nationalism can be a useful tool for crafting a political agenda for a given group, it “becomes reactionary because it is totally inadequate for surviving in the world with many peoples.”25 You can’t be in coalition all the time, of course: commitment to coalition means also having a home space somewhere else, where you can be comfortable, “so that you will not become a martyr to the coalition.”26 But return to coalition you must, if you want to shape the future. She encouraged her audience to think of the long game: “What would you be like if you had white hair and had not given up your principles?”27

The Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention was, truly, a project of coalition: electrifying, uncomfortable, chaotic, demanding. In that light, the Radicalesbians’ retreat to separatism is as understandable as it is disappointing. I don’t doubt for a second that sexism and homophobia were present at the convention, as, surely, were racism, classism, ableism, and so on. After all, every person there was a product of their society, as are we today. Coalition demands everything you’ve got, but what other choice do we have? The work’s not finished yet.

Jared Leighton, “All of Us Are Unapprehended Felons,” Journal of Social History 52, no. 3 (2019): 868.

Leighton, 871.

Alas, I accessed these documents through ProQuest using my Harvard institutional login, so I can’t link to them directly. But their official title is “FBI COINTELPRO surveillance files covering Black Panther Party, James Forman, Eldridge Cleaver, Huey Newton, Revolutionary People's Constitutional Convention, National Committee to Combat Fascism, Venceremos Brigade, SNCC, and RNA,” from COINTELPRO Black Extremist Files (Dec 1, 1970-Jan 31, 1971).

Marc Stein, City of Brotherly and Sisterly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia, 1945-1972 (2004), 333.

George Katsiaficas, “Organization and Movement: The Case of the Black Panther Party and the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention of 1970,” in Liberation, Imagination, and the Black Panther Party: A New Look at the Black Panthers and their Legacy (2001), 146.

Katsiaficas, 146.

Katsiaficas, 147.

Katsiaficas, 148.

“the days belonged to the panthers,” off our backs 1, no. 11 (September 30, 1970): 4.

Stein, 333.

Stein, 334.

Stein, 334.

Stein, 334.

“lesbian testimony,” off our backs 1, no. 11 (September 30, 1970): 4.

“lesbian testimony,” 5.

“lesbian testimony,” 5. I believe that YAWF refers to Youth Against War and Fascism, a subgroup of the Worker’s World Party.

Stein, 337.

Stein, 337.

Stein, 336.

Bernice Johnson Reagon, “Coalition Politics: Turning the Century,” 115 (this version).

Reagon, 115.

Reagon, 116.

Reagon, 116.

Reaon, 118.

Reagon, 118. This line makes me cry.

Abolishing the nuclear family is a fascinating sticking point of contention: makes me wonder if, if this type of thing happened today, would that still be a big sticking point? It's sorta infeasible as an actionable item: you can make positive changes to support other kinship structures, but you can't just make one illegal. Would people even care enough about that compared to other things?

It's also interesting to see how sure, romantically, this BPP-era coalition work felt so simple and strong and understanding of different perspectives, but there's also that huge element of Party Line, Marxist dogma, anyone who troubles the message and movement is a bourgeoisie revisionist, etc. It was hard and exhausting then too. What's different today that's cut off some avenues, but opened wiggle room elsewhere?

This reminds me of that great line from Fred Moten about coalition:

"Yeah, well, the ones who happily claim and embrace their own sense of themselves as privileged ain’t my primary concern. I don’t worry about them first. But, I would love it if they got to the point where they had the capacity to worry about themselves. Because then maybe we could talk. That’s like that Fred Hampton shit: he’d be like, “white power to white people. Black power to black people.” What I think he meant is, “look: the problematic of coalition is that coalition isn’t something that emerges so that you can come help me, a maneuver that always gets traced back to your own interests. The coalition emerges out of your recognition that it’s fucked up for you, in the same way that we’ve already recognized that it’s fucked up for us. I don’t need your help. I just need you to recognize that this shit is killing you, too, however much more softly, you stupid motherfucker, you know?”"