Hi homos! Last week I completed the first chapter of my dissertation (pending my advisors’ approval…), which is about how trans people were involved in the women’s music community and why women’s music became a hotbed of conflict over trans participation in lesbian feminist spaces. I won’t rehash my whole argument there (I’m hoping to publish it elsewhere!), but I thought it would be fun to share a short history of women’s music and some songs that I like.

What is women’s music, you ask? You’ve probably already hear of its most famous venue - the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. In fact, I’m planning to follow this up with a newsletter specifically about MichFest and Camp Trans, the group activists who tried to get the festival to retract its “womyn-born-womyn only” policy. Their efforts ultimately did not succeed, and the festival was cancelled for good in 2015. This was not the goal of the Camp Trans activists; they wanted the festival to continue, with a trans-inclusive policy! That is to say, women’s music was important to them, as it has been to a great number of women and queers.

The term “women’s music” might sound odd to our modern ears - so broad! It makes more sense when you think about the context from which it originated. In the early 1970s, women who were forming the nascent women’s liberation movement, including burgeoning lesbian feminists, were developing new languages and frameworks that they could apply to various aspects of culture and society in order to consider how all parts of modern life had been shaped by patriarchal forces. Music was no different - all popular music had to pass through the hands of (basically all white) men, from studio sound engineers to record label executives to radio programmers to the owners and bookers of music venues. All popular music then, even when it was performed by a woman singer, was ultimately controlled by men. Women’s music was less a genre than a movement that responded to that simple fact. It posed the question: what would music sound like if all those roles, or as very many of them as possible, were filled instead by women?

At its core, women’s music was music for women, by women, and about women. This included lots of lesbian love songs and songs about lesbian life, of course! For many curious audience members attending women’s music concerts, it was electrifying to hear lesbian relationships and identity being sung about in explicit terms. Max Feldman’s “Angry Atthis,” which was first performed in 1969, is broadly considered the first “out” lesbian song of the women’s music movement, and it provided many audience members the experience of hearing the word “lesbian” sung or spoken from a stage.

Feldman, as it happens, is a part of the trans history of women’s music as well. A self-described “big loud Jewish butch,” he transitioned later in life to primarily using he/him pronouns and shortening his name from Maxine to Max. His presence here, then, complicates the concept of women’s music as “by, for, and about women” - "women” was both a useful category around which to organize against patriarchy and insufficient as an endpoint for categorization of all who participated in these efforts. Feldman’s transition was publicly acknowledged in his obituary, when he died in 2007 at the age of 62. “Angry Atthis” is a potent document of the hardships of lesbian life in the late 1960s, including the dangers of visibility and the pain of hiding. But he made more celebratory and lighthearted music too!

Women’s music began to coalesce as a style and a scene during the early 70s, and in 1973 the first women’s music record label was founded: Olivia Records. Olivia was run by a group that spawned from the D.C. radical lesbian collective The Furies. They operated collectively, and were pretty strictly separatist, meaning that they only directly employed women (mostly lesbians), and they only worked with women to the furthest extent possible. Distributing records to male-owned record stores, for example, was done in areas where women-owned stores were not available, but it was not preferred and was the source of some contention among hard-core separatists.

I’ve written a bit about Olivia Records here, focussing on the collective’s response to transphobic efforts to oust Sandy Stone, a trans woman who joined the collective as a sound engineer. But there’s much, much more to the Olivia story, and if you’re really interested in Olivia/women’s music, I encourage you to read Olivia on the Record by Ginny Berson, a memoir about the founding and early years of the company. Olivia was not only the first women’s music label, but also arguably the most high-profile throughout the 70s and early 80s. Meg Christian and Cris Williamson, two of the most well-known women’s music artists, were with Olivia from its founding. Cris Williamson’s “Waterfall” was a women’s music hit, for good reason! It’s a personal-growth banger!

Fun note- when Olivia approached Sandy Stone to recruit her, Cris Williamson’s album The Changer and the Changed, which she was familiar with, helped convince her to join. She loved Williamson’s voice and songwriting, but she thought the mixing was shit! She remixed the album during her time at Olivia. When I interviewed her, she told me that Williamson’s “Sister” was her favorite song that she worked on at Olivia. She called the experience of recording it “spiritual.”

Like many (though not all!) 70s lesbian organizations, Olivia was founded by white, middle-class women. Again, like many fellow organization, the original Olivia members sought to collaborate with women of color and working-class women, to mixed success. While the difficulty of creating truly diverse lesbian organizations was a site of ongoing frustration to women across race and class lines, Olivia did diversify over the course of the 70s, and it produced important works by Black artists. Singer Mary Watkins, singer and producer Linda Tillery, singer Gwen Avery, and poet Pat Parker were among Black artists who worked with Olivia, and this group put on a successful national tour in 1978 called “The Varied Voices of Black Women.” Meanwhile, white working-class artists like Teresa Trull and band BeBe K’Roche also brought class awareness to their work with the group. Below are a Mary Watkins song I quite like (which contains a lyric about hiking boots…gay), as well as a song by Teresa Trull. Note that some hard-core separatists who, among other things, aimed to oust Sandy, criticized Trull for being too close to “cock rock” for playing an electric guitar while touring for this album. Insane.

Though the stereotypical white women’s music artist continued to be a singer-songwriter with an acoustic guitar, Black artists expanded the sound of women’s music and brought with them a broader range of influences. Bernice Johnson Reagon’s group Sweet Honey in the Rock, an ensemble of all Black women that continues to perform today with an evolving lineup, toured in women’s music venues and festivals and gathered a large women’s music fanbase. At a 1981 women’s music festival, Johnson Reagon burned the house down with a speech about coalition politics, which she later published as an now-seminal essay in the 1983 anthology Home Girls. A friend of mine, when listening my YouTube women’s music playlist, was surprised to see Sweet Honey in the Rock there - he thought of the group as working in a Black gospel tradition and hadn’t thought of them as situated in a feminist music tradition. But of course both are true!

Here is a performance of Sweet Honey in the Rock’s “Ella’s Song,” composed from the writings of Ella Baker.

And here is a song by Johnson Reagon about Joan Little, a Black woman who was charged in 1974 with first-degree murder for killing a white prison guard when he attempted to rape her. Little was facing the death penalty, and her cause was taken up broadly by feminists across the U.S. and became a site of important multiracial coalition work. Thanks in significant part to their work, Little was acquitted, and she was the first woman in U.S. history to be acquitted of murder on the grounds of self-defense from sexual assault.

And women’s music artists of course continued to create work advocating for lesbian and gay rights. Holly Near, who has participated in an impressive number of activist causes over the course of her long career, has this gay rights banger:

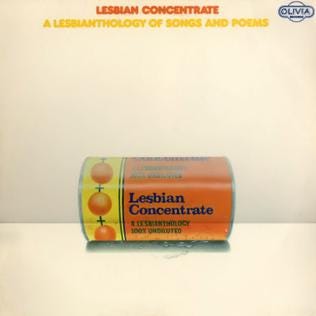

And here’s a poem by Pat Parker, who released spoken word records with Olivia. This poem was included on Lesbian Concentrate, a compilation record put out by Olivia in 1977 in response to Anita Bryant’s anti-gay campaign:

While a lot of women’s music could be quite political and serious, it also provided a space for playfulness and fun - and sometimes all of the above, all at once! I’ll finish with a delightful track by the trans musician Beth Elliott that perfectly encapsulates this combination:

XO!

I’m an old lesbian and poor. Enjoyed this read and listen. Gwen Avery cut my hair for years. Holly and Cris come perform in my little Olympic Peninsula town. We all miss Meg so very much. West coast-centric, there were wondrous musicians and poets in the East. And never forget Kay Gardener with her flute down by the river in Yosemite at the excellent West Coast Women’s Music Festival.

Check out Ellen Bonjorno and her Sing It, Sister show on KPTZ.

Thanks for these memories...