Womanhood and Common Sense

Tell me you know what a woman is and I'll show you a liar

Note: transphobia is discussed in this essay! If you would rather not read about it, then you should skip this one.

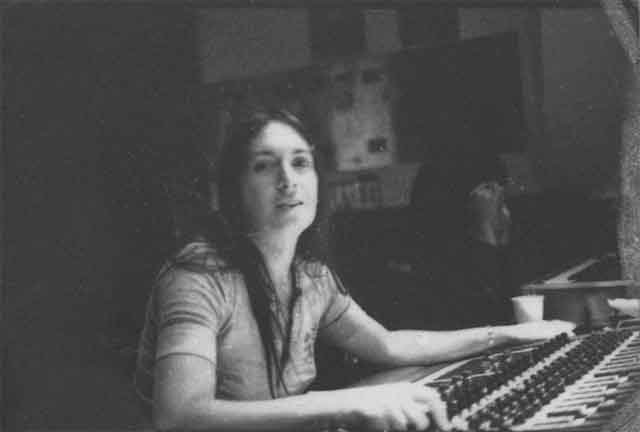

The other month, I visited the Smith archives in Northampton to check out their materials from Olivia Records. Olivia was the first record label created exclusively to produce women’s music, a largely lesbian musical movement made by, for, and about women. (Side note: Olivia later pivoted to become a lesbian cruise line, notably featured on a Season 2 episode of the L Word.) Olivia was a separatist endeavor, meaning that they only hired and recorded women, almost all lesbians, and all with avowedly feminist politics. In 1974, Olivia Records began working with Sandy Stone, a sound engineer who had previously worked with the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Crosby, Stills and Nash. Stone is a trans woman, and the Olivia collective discussed the implications of including a trans women within their separatist framework before beginning to work with her. Ultimately, they decided, Stone had foregone a great deal of privilege by transitioning, and she was committed to life as a woman and to feminist politics. What was a woman? That question didn’t need to be conclusively answered in order for the collective to see that, by the measures that mattered to them most, Stone was one.

In 1976, Janice Raymond mailed the Olivia collective a chapter of her forthcoming book The Transsexual Empire, a foundational screed of modern transphobic thought. The chapter blasted Stone, and word had begun to spread within the Olivia orbit that they had hired a trans woman. Olivia sent a statement, signed by cofounder Ginny Berson, to their distributor network explaining that Stone was indeed trans, and that they had not felt that this was something that needed to be disclosed to the broader community because it did not impact them. “In evaluating who we will trust as a close ally, we take a person’s history into consideration, but our focus as political lesbians is what her actions are now,” the letter reads. “We felt that Sandy met those same criteria that we apply to any woman with whom we plan to work closely…She has chosen to make her life with us, and we expect to grow old together working and sharing.”

In the Smith Archives, in a folder titled “Correspondence Re: Sandy Stone,” I read this letter, and two others exchanged shortly after. A letter from a distributor in Cleveland named Lori, addressed to the whole Olivia collective, conveyed a profound sense of anger and betrayal in response to the knowledge that Stone was trans, which she had learned by word of mouth a few months earlier. The focus of her ire was the collective’s choice not to publicly disclose Stone's transsexuality to the greater community before hiring her, and to put this matter up for community debate. To contextualize this a bit, open community debate was basically the modus operandi of lesbian feminism. Olivia had a newsletter that was circulated amongst distributors where they did indeed often share news about internal conflicts and publish letters they received on all sides of any given issue, including letters complaining about things that the collective had done. Stone’s hiring was not something that was presented for debate in this way.

Lori’s letter makes it clear that she believed her anger was widely shared, and she conveys disbelief that the Olivia women could really have believed that the hiring of Stone would not become a large-scale issue. She writes:

“Since such a great many wimmin are upset with Olivia right now, that indicates to me a lack of responsiveness to wimmin’s needs (which, of course, vary so much that nothing will meet all wimmin’s needs)…I am sure that Sandy has many skills to teach wimmin, and in your personal dealings with [her] you have felt Sandy to be relating to you as one womon to another, and that’s ok— but I’m feeling somewhat distrustful; I’m not exactly sure of what, except that I can’t assume anymore that I will agree with your political judgment.”

The degree of hedging here is almost comical to me; the letter bounces back and forth between complete outrage and deep uncertainty about whether Olivia’s decision actually perfectly fine, arriving at a conclusion of, well, you should have TOLD me first!

In a response letter, Ginny Berson is delightfully dismissive of Lori’s whole deal. Berson writes:

“Stone became an issue because there are several women who have been out to get Olivia for quite a while, for not being separatist enough. It is infuriating to me that because of this one thing women are no longer supportive of Olivia. Support sure is easily given and easily taken away.”

In response to distributor’s implication that she was speaking for a broad array of outraged women, Berson says:

“There is no current onslaught of outrage against Olivia that I am aware of. Most of the communication we’ve had on the subject has been positive or supportive of Olivia. Most women that have written or called or have spoken up in workshops feel that either it doesn’t matter to them one way or another that Sandy is a transsexual, or that it basically isn’t any of their business anyway.”

Signing off, she says, “I don’t know what your options are, except that it is not an option for you to distribute Olivia Records and not consider us an all-women’s record company. So if that’s where you’re at, then I guess this is it.”

Reading this, I was struck by the fact that what Berson and Lori were struggling over was, in large part, the terrain of common sense within lesbian feminist community. Women-only spaces were important: on this, they agreed. But Lori, while not quite willing to claim that trans people could not be women, claimed as common sense the notion that the inclusion of a trans woman in women’s spaces was inherently controversial enough that it should obviously be put to the greater public for debate. Meanwhile, Berson claimed a different set of common-sense principles: that if someone lived as a women and struggled politically alongside other women, then that person was a woman and a sister, deserving of care and protection from her community. Her well-being could not be sacrificed in the name of outside demands; this was antithetical to the foundational principles of women’s liberation. Additionally, Berson rejected Lori’s claim that the community was broadly upset about Stone. Obviously, I don’t have the data to show who was “right” about this, but it’s worth taking seriously that, from Berson’s point of view, the average response to Stone’s inclusion was supportive or neutral. Today, most people would probably assume that Lori’s version of common sense was far more typical of lesbian feminists of that era, but plenty of sources (such as Berson’s letter) suggest otherwise.

As is tragically so often the case, the transphobes were organized, and Stone would eventually voluntarily leave the collective amidst threats of boycott, despite the Olivia collective continuing to insist that they wished for her to stay. She would go on to become a computer programmer, a media theorist, a performance artist, and a foremother of trans studies via her canonical essay “The Empire Strikes Back” (a retort to Raymond’s The Transsexual Empire). The issue of who gets to determine the parameters of common sense about gender within lesbian and feminist spaces would, of course, remain unsettled, and struggles continue over this terrain.

Here’s where I will pivot to my thoughts on the landscape of queer common sense today. Entering queer community from a straight upbringing generally requires replacing old common-sense notions and rules of politeness with new ones. In the place where you grew up, it perhaps was polite to call people “sir” or “ma’am.” In the spaces you run in now, it may be polite to “they/them” people until their pronouns have been confirmed to you. These are two different sets of rules. Both are learned, and both are wedded to broadly shared notions about gender that are rooted in a communal common sense. Both are ways of showing respect, and both have their limitations.

Practices that originated in resistance to straight common sense become their own codes. This makes sense, and it to some degree occurs by design. We need codes of politeness and shared common sense norms in order to exist in society. But something is lost when we pretend that the codes and common knowledges that attend our political orientations are obvious. We conceal the great degree of work that it took to get us there: both our own work and the work of others. Reading the writings of women involved in Olivia and other cis and trans women struggling toward trans-inclusive feminism during the 1970s has illuminated this for me. They didn’t have a road-map, just reason and principle. And friendship.

I remember sitting in the library in college, agonizing over a printed copy of the introduction to Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble. As you may well know, this is where Butler presents their theory of performativity as it pertains to gender and sex. Gender, they argue, is an imitation without an original. The categories of woman and man/male and female exist only as they are enacted, through a near-infinite number of gestures, everyday. Sex, too, is socially constructed, Butler argues. Sure, there are bodies with differences and similarities, but there’s no way to disentangle what we call biological sex from the the many layers of gendered meaning that we have placed upon the body. There’s obviously a lot more to it than that, and it’s a typically Butlerian complicated set of ideas presented in difficult prose. Reading each sentence was, for my nineteen-year-old self, a Herculean struggle. Then, suddenly, it clicked. Butler’s argument came into focus. I cried onto my printout in a private moment of ecstasy.

It’s interesting to track, in the more than ten years since then, how the idea of gender performativity has seeped into common sense amongst queer young people. I’m fairly confident that if I asked most of my queer students what gender performativity was, they would give an answer about how gender is fake. Indeed, Butler had to publish a whole book (Bodies that Matter) in response to misreadings of their work that accused them of trivializing gender as a daily choice rather than (as they were really saying) a compulsory system of imitation and iteration that we are all ultimately trapped within.

Perhaps I’m reading my students ungenerously here. And I’m certainly not saying that everyone has to read Butler before they speak about gender as performance. What I am arguing for, I suppose, is an ongoing critical engagement with our own common-sense ideas about sex, gender, and sexuality. Where did they come from? How did we learn them? What are they doing for us?

In the time since the Lorie wrote her outraged letter to Olivia, the transphobes have grown much, much more certain of their ideologies, packaged as common sense. Think of Ketanji Brown Jackson’s congressional hearings: the right mocked her endlessly for her inability (or refusal) to define the word “woman.” Committed bio-essentialists know their definition of woman, and it’s “person who was born with a vagina.” (The existence of intersex people, etc. is, for these people, an exception that does not disrupt the rule.) A common-sense definition of woman, coming from someone left of center, might be “person who identifies as a woman”: a fine principle, but a circular definition. Our common sense might fail us here, and maybe it’s a failure worth embracing.

The truth is, I don’t know what a woman is and I am one. I know that being a woman can mean strongly identifying with womanhood, or feeling a deep ambivalence toward womanhood, or both, or neither. I know that my womanhood is related to my body but not dictated by it. I know that womanhood is relational, and that to exist as a woman or man or any other gender means constantly honing oneself against the logics of binary gender and heterosexuality, however you may choose to relate to those things. Womanhood, I know, is always riffing on its own history. I know that gender, when it is felt freely, can be a source of pleasure. I know that gender is social; if I’d spent my whole life alone in a cave, I wouldn’t be a woman. Then again, if left alone in a cave, I would’ve died as an infant.

The deception of common sense, when it comes to these things, is that implies its own universality, when in fact near everything about gender and sexuality as they are lived is contingent. What I admire most about many of the people I am writing about in my dissertation, both trans and cis, is their willingness to be unsure about who or what or how a woman might be, their bravery in allowing their understandings to evolve, and their commitment not to explore these questions at someone else’s expense. For me, being a generous historian means understanding that these things take courage and dedication, then as now.

PS: If you’re interested in learning more about the history of Olivia Records and/or Sandy Stone’s time there, I really loved and learned so much from Ginny Berson’s memoir Olivia on the Record and this interview with Sandy Stone by Zackary Drucker.