A Theory of the Sapphic

Sappho was a right-on womxn

I recently had a conversation with my academic advisor, a lesbian who came of age in the 80s, about evolving lesbian terminologies. It was a delightful moment of intergenerational revelry in the evolving particulars of our shared lesbian culture. “Young people are using the word ‘sapphic?!’” she asked, in disbelief. Yes, I answered, and tried to explain the specific charge that “sapphic” holds for young people in this particular moment. “Sapphic” is mostly used by people younger than me, I noted (I am thirty-one, for the record). “Sapphic” carries an air of inclusivity across sexual and gender identities; it is used to describe bisexual and nonbinary people, for example. “Sapphic,” in my experience, skews white, but not exclusively so. “Sapphic” is most often used as a modifier to describe media and spaces (sapphic romance novel! sapphic dance party!) but is also used to describe people. “Sapphic” is even sometimes used as a noun - this one blew my advisor’s mind.

Here is where I may risk alienating you, my dear reader! In truth, I told my advisor, I chafe a little at “sapphic.” Something about it feels a bit twee, a bit tender-queer, a bit overly-invested in creating identification through media and cultural signifiers rather than through desire and the messy business of living. If an event is billed as “sapphic,” I by and large feel that it is probably not for me; for one thing, there is a strong chance that everyone there will be significantly younger than me. Maybe my issue boils down to discomfort with the generational difference between myself and queer Zoomers in their twenties: our ages are not so far apart, but in queer years, the gulf can feel large. Really, I told my advisor, my trouble with “sapphic" is that it feels, well, unsexy.

Now, this surprised her! In the eighties, she told me, “sapphic” was mostly used to describe sex. If I see an event billed as sapphic, I assume it will be a poetry reading featuring lots of jokes about polyamory.1 If she saw an event billed as sapphic, she would assume it was an orgy.

This got me thinking. The two of us, both lesbians, had clear associations with “sapphic,” but those associations were very different from each other. Neither of us identified with the term. Clearly, “sapphic” has cycled in and out of use in lesbian and adjacent communities over the years. But is there a pattern to this cycle? Is there a guiding principle that has governed when “sapphic” has come in and out of use and who has been drawn to it? This newsletter is my non-exhaustive attempt to answer this question!

Now, let’s start with the fact that “sapphic” and “lesbian” are drawn from the same referent: namely, the poet Sappho who lived on the Greek island of Lesbos, circa 570-630 BCE. Sappho’s poems, as you likely know, survive only in fragments that have been translated many times over the years but perhaps most dykishly in the modern era by Anne Carson.

I won’t subject you to a long, Wikipedia-based history of the evolution of Sappho’s legacy and reception, but suffice it to say that her poems have not always been read as evidencing homosexuality - over the last several centuries, she has been portrayed by scholars and critics as a tragic lover jilted by a man, a straight slut, a bicon, and even a beacon of chastity, as well as a massive homo. Her modern status as a symbol of female homosexuality in the Western canon began to solidify in the late 19th century. A new English translation of Sappho’s poems by Henry Wharton, published in 1885, inspired English-speaking lesbians such as Katherine Harris Bradley and Edith Emma Cooper, who published poetry together under the joint pen name Michael Field, to engage with her work. Bradley and Cooper (hmm) were an aunt and niece and also LOVERS who lived together for 40 years. Sorry, deal with it. Anyway, their poems both drew on Sappho’s fragments and were horny.

The use of “lesbian” to refer to gay women basically originates from around the same time, and was used interchangeably in Victorian sexological literature with “sapphic,” “sapphist,” “invert,” and “homosexual.” In the twentieth century U.S, “lesbian” continued to be used as an adjective and noun for gay women in medical literature, but it’s my understanding that in a lot of pre-1960s lesbian communities, “gay” or “gay girl” were the primary terms by which women referred to themselves. It was in lesbian feminist communities in the late 1960s and into the 1970s that “lesbian” really solidified as a term of identity, not just a description of behavior. A quick Google Ngram search comparing the usage of the two words in books over time shows that the usage of “lesbian” takes off starting in the 1960s, leaving “sapphic” in the dust.

Now, I’m not totally sure why “lesbian” took primacy over “sapphic” as the main term of identity used by anglophone gay women. However, if I had to guess, I would wager that it has to do with the clear reference that “sapphic” makes to one individual. Even though the origin of “lesbian” obviously also refers to Sappho, the term feels a bit more general. Side note: while doing this research, I learned that in 2008 a group of Lesbos residents took a gay rights org in Greece to court (and lost) for their use of the term “lesbian,” claiming that Lesbos islanders should hold sole use of the term. Lol.

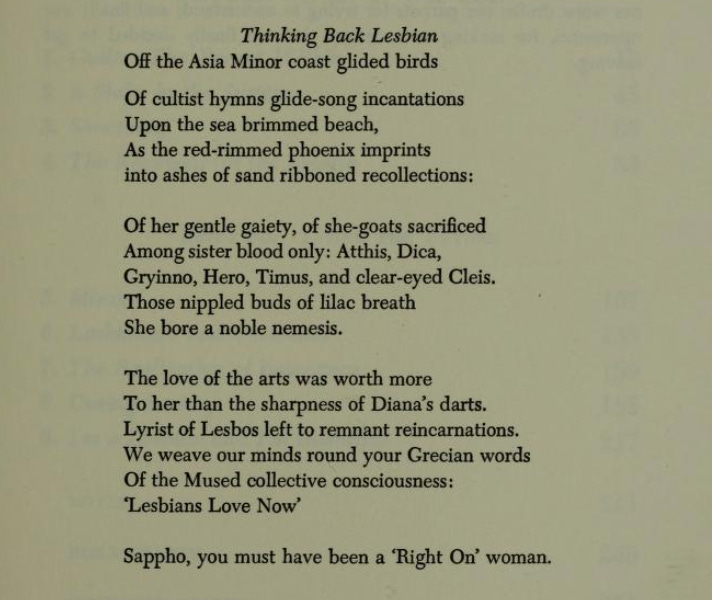

Although “lesbian” has obviously become the primary term for gay women, “sapphic” has faded in and out of popularity over the years. In 1972, Sidney Abbott and Barbara Love published an influential book called Sappho Was a Right-On Woman: A Liberated View of Lesbianism, its title drawn from a poem by Sue Schneider:

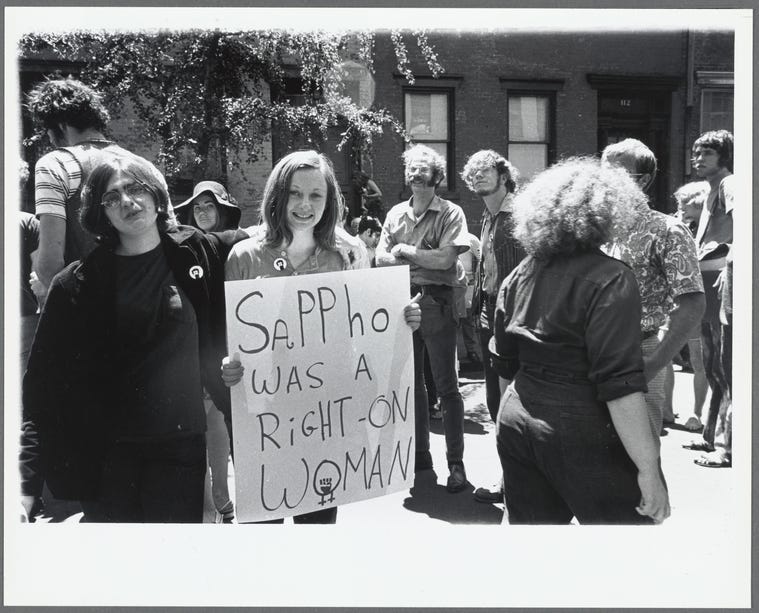

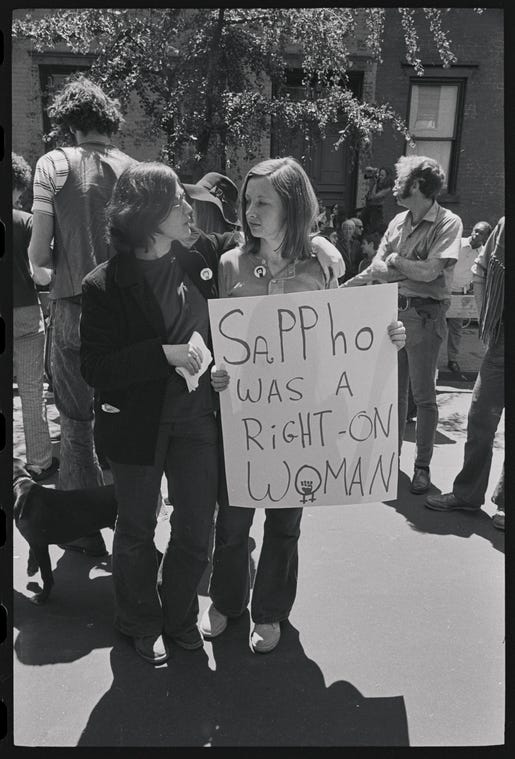

Abbott and Love were coming from the Gay Liberation movement, and they wrote their book in a moment where almost no published written material by and about lesbians existed. Their book attempted to capture both the culture of homophobia and repression that lesbians were just beginning to resist, and their hopes for a liberated future. A photo from a 1970 gay pride event, one year after Stonewall, shows two women holding a sign with the slogan, proving that this slogan was in circulation prior to the publication of the book:

I also found a veryyyy DIY lesbian magazine from the early 1970s called Echo of Sappho, which was dedicated “to the memory of Sappho":

Notably, none of these materials feature the word “sapphic”; rather, they refer to Sappho herself, as a historical figure. The utility of this reference in the historical context of the early 1970s makes sense. These women were struggling to create a vision (and a reality) of liberated, unashamed, unrepressed lesbian life, for which they had essentially no model. Sappho represented something like a historical predecessor, a figure who showed that lesbian sexuality had a long history and even a place within the revered Western canon.

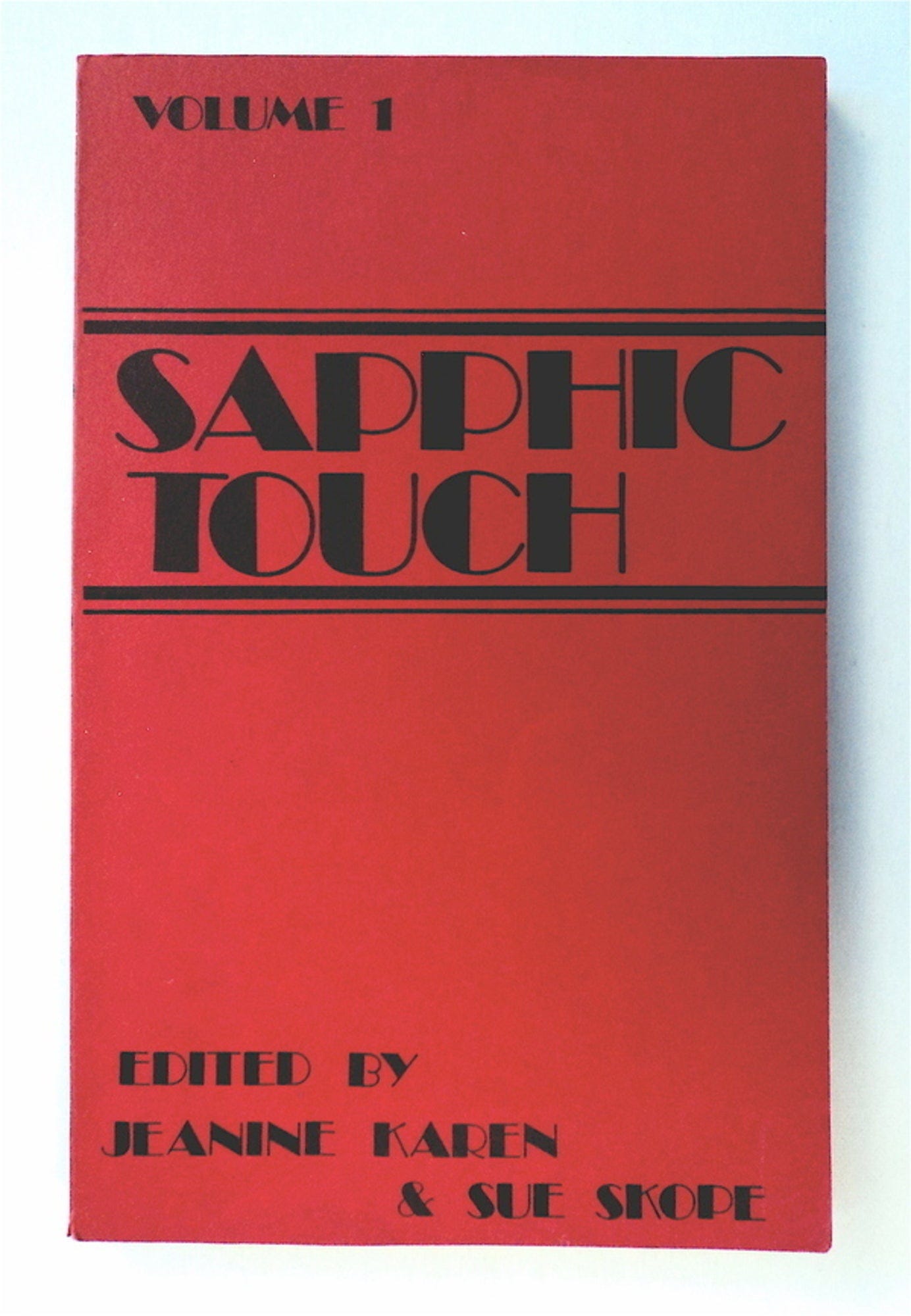

Fast-fowarding into the 1980s and 90s, I found some evidence to support my advisor’s memory that “sapphic” during this era connoted sex. Specifically, here’s the cover of a 1981 volume of lesbian erotica:

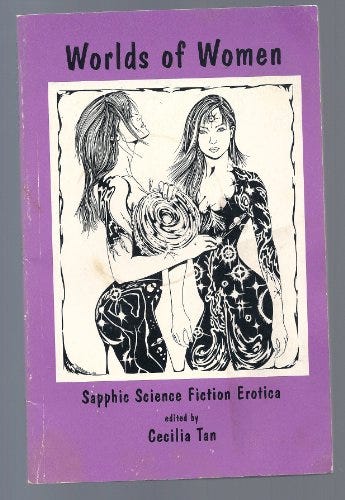

And here’s a zine by Cecilia Tan from 1993, which looks absolutely sick:

You can find copies of both of these floating around for sale, by the way! Anyway, I wasn’t able to find a ton of other evidence of this use of “sapphic.” That doesn’t mean, however, that my advisor’s perception wasn’t correct! Keep in mind that a lot of cultural ephemera, like event flyers and t-shirts, let alone word-of-mouth communications and everyday speech, don’t get archived. Plus, tons of archived materials are not digitized. It’s also possible that this use of “sapphic” was more localized.

In the aughts, I noticed that “sapphic” sprung up in several titles of academic books: the anthology Sapphic Modernities (2006), Lisa Duggan’s Sapphic Slashers (2000), Robin Hackett’s Sapphic Primitivism (2004). I wonder if “sapphic” was an appealing word choice to these authors because it allowed them to gesture at gay women’s life outside of or before modern lesbian identity. It seems like, during this era, “sapphic” was not used much in more vernacular or pop-cultural settings, so perhaps the word felt relatively free of modern baggage to scholars.

The current resurgence of “sapphic” dates back at least a few years; Autostraddle published an explainer article in 2021 discussing the trend (worth a read, if you’re interested in this topic). I feel like “sapphic” really flourished in the meme space around this time. You probably know what I’m talking about, but here are a couple examples.

Chandra, the author of the Autostraddle article, polled a bunch of people about their uses of “sapphic,” and their stated reasons for using it were aligned with what I would imagine: people use “sapphic” mainly to describe media and events/spaces rather than individuals, and it’s typically used because it’s perceived to be more inclusive than “lesbian.” This all tracks, but it doesn’t answer the question of why “sapphic” appears to be more inclusive than “lesbian.” This is where I will offer my own theory of “sapphic” and its appeal.

My theory is this: “sapphic” offers an escape hatch from whatever the perceived main problem with “lesbian” appears to be in a given historical moment. For example, as I have discussed, “sapphic” was used in at least some instances to convey eroticism in the 1980s and 90s, which, you may recall, was the Sex Wars era. Perhaps “sapphic,” during this time, offered an escape from the all-politics-no-sex vibes perceived to be emanating from “lesbian,” which some dykes were interested in escaping.

I would argue that the main “problem with lesbian” today (and I use quotes here to demarcate that I am discussing this "problem” not in its material reality but in its existence as a widespread perception) is a problem of inclusivity. “Lesbian” is poised as a subject of critique by and large for who it does or does not include; for who claims it or is claimed by it, and who is not. “Sapphic,” which historically has been used synonymously with “lesbian,” now offers an escape hatch from this inclusivity problem, even though there’s no inherent reason why “sapphic romance novel,” “sapphic space,” or “sapphic tendencies” would translate to greater inclusion than “lesbian romance novel,” “lesbian space,” or “lesbian tendencies.” What the 1980s and 90s anxieties about lesbian eroticism (or lack thereof) and contemporary anxieties about lesbian inclusion (or lack thereof) have in common is a concern with the baggage of lesbian history and its consequences. Have decades of feminist critique made us sexless? Does a history of trans exclusion make us irredeemably backwards? What both of these questions miss is that the counter-history has been there all along: slutty and smutty lesbians, trans lesbians and their cis lovers, friends, and allies, and so on.

Now, let me be clear! Everyone should use the words they like! This is but one woman’s theory, and I invite you to disagree. I am not here to hate on “sapphic” and those who like to use it, even though I won’t be joining you. Ultimately, this has been my attempt to elucidate why “sapphic” has an edge that makes me want, a little bit, to turn away from it. The reason is this: I love parsing lesbian history, in all its troubles and messes. It’s a history I do not wish to escape.

This is a self-own, by the way, if you’re following along with the Val’s social calendar.

I get the sense that when you talk about sapphic as being perceived more inclusive you are referencing specifically trans inclusion. For me, a big part of the inclusivity of sapphic vs lesbian is including non-monosexual identities e.g. bisexual/pansexual. I'm a bisexual about to marry a lesbian and if a space / event / opportunity is described as "lesbian" I will assume it is not a space for me, whereas a "sapphic" space / event / opportunity would include me.

I like it because it feels really inclusive. I'm a Transfeminine Sapphic Gen X Riot Grrrl Dyke. Happy Pride month!