I was twenty years old in Tokyo, visiting my friend who was there studying abroad. She had homework to do; she had a host family whose rules she needed to respect. I was backpacking and staying in a hostel; I wanted to party. One night when she was busy, I went out with some girls she had introduced me to, college students from England. These friends-for-the-night took me to a gay club in Shinjuku. As far as I knew they were straight, but that’s never stopped anyone from partying at a gay club if they want to.

As I made my way through a sweaty crowd of mostly men, another girl and I brushed past each other on the steps leading down to the dance floor. Everything slowed down for a moment as our eyes raked each other’s bodies from head to toe, examining clothes, waist, shoes, tits, face, collarbone, hair. And then she swished past me and was gone. I turned back to the two English girls and they were both staring at me, mouths agape. “What was that?”

I’ve checked out many women over the years, and I’ve felt another woman’s eyes travel over me in this lustful, appraising way plenty of times before. But this one particular moment sticks in my memory perhaps because it was maybe the only time when such a moment was clocked by a straight companion – or maybe just the only time a straight companion has said something about it. I, of course, was utterly pleased with myself, and rightly so. After a long adolescence of pent-up desires, I had finally initiated myself into a silent language of the eyes. I saw her and she saw me.

Well, what was that?

Cruising is but one technology that queers have developed to find each other. In 2019, we gained another; it’s called Lex. If you are reading this newsletter, you are presumably familiar with Lex, a text-based, lesbian-ish dating app born out of a lesbian personals account on Instagram, now rebranded as an app for connecting with “LGBTQ+ community.” If you have used Lex, you are probably aware of its incredible strangeness. Much like my companions at the club in Tokyo, I believe that most straight people would have their minds blown if they saw what goes on on the app. I’ve been trying sporatically for three years to pitch an essay about Lex to various publications, and I have not succeeded. This is probably in part because I’m bad at pitching, but I think it’s also because it’s hard to get people who haven’t used Lex to care about it.

I believe that Lex, in its history, its design, its community norms, its conflicts, is one of the richest lesbian cultural objects today. It is embedded on every level with the history of lesbian community conflicts reborn anew with each generation; its failures and successes can tell us much about where “we” (lesbians? queers? LGBT+ community?) are in this moment in history. So I’ve decided to finally just write about it here, chez moi. As usual, I’ve got too much to say, so this will be a three-parter. This first part will relay a brief(ish) history of the Feminist Sex Wars, a period of feminist community conflict spanning from the 1970s to the 1990s. The second part will build on this history to explore how Lex is situated, both intentionally and unintentionally, in relation to Sex Wars aesthetics and politics. I’ll also explore why the Sex Wars seems to draw a certain type of lesbian nostalgia, due to its particular set of similarities and differences to our contemporary moment. The third and (I think…) final newsletter will take a closer look at the culture(s) and norms found on Lex, including some of your stories and takes. So it’s not too late to send me those if you haven’t already! And thanks so much to those of you who have emailed. I have thoroughly enjoyed every one of your messages.

Born in Flames: A Brief History of the Sex Wars

In the 1970s, the women’s movement was engaged in active critique of nearly all aspects of contemporary culture; pretty much every facet of society, feminists argued, was shaped in one way or another by patriarchy. Feminism, in its most radical and expansive form, was interested in reshaping human relations. But what should be the new shape?

Lesbian feminist communities incubated conversations and debates about whether heterosexual relations could ever be non-patriarchal; about the radical potential of disinvesting from male desire; about what might become possible when women re-oriented their erotic and sexual selves toward other women. Out of these conversation emerged a line of feminist critique and activism focused on opposing pornography and sexualized depictions of violence against women. The 1976 film Snuff, which falsely purported to show the real murder of a woman, galvanized a wave of activism that began to coalesce into a recognizable anti-pornography sub-movement within the larger feminism movement. Andrea Dworkin, who would become perhaps the most well-known leader of the anti-porn feminist faction, organized protests of Snuff in New York, and the film spurred the formation of groups in San Francisco and Los Angeles in opposition to depictions of violence against women.

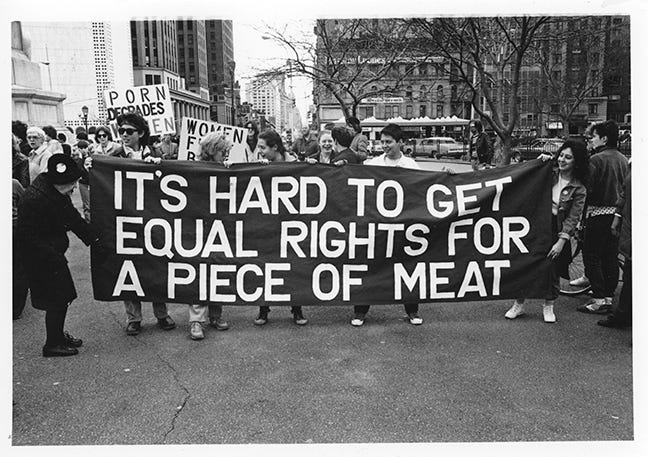

The anti-porn feminists were focused on cultural change, but also legal change; Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon, a high-profile anti-porn lawyer and legal scholar, would draft an Antipornography Legal Rights Ordinance in 1983, which proposed to classify pornography as an infringement on the civil rights of women and allow women harmed by pornography to press charges. The anti-porn faction grew to include anti-BDSM and anti-sex-work activism. This led, in part, to confrontations between anti-porn activists and woman sex workers. For example, Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media (WAVPM), a San Francisco group, picketed a strip club that featured girl-on-girl BDSM performances as their first action. You can see where this is going.

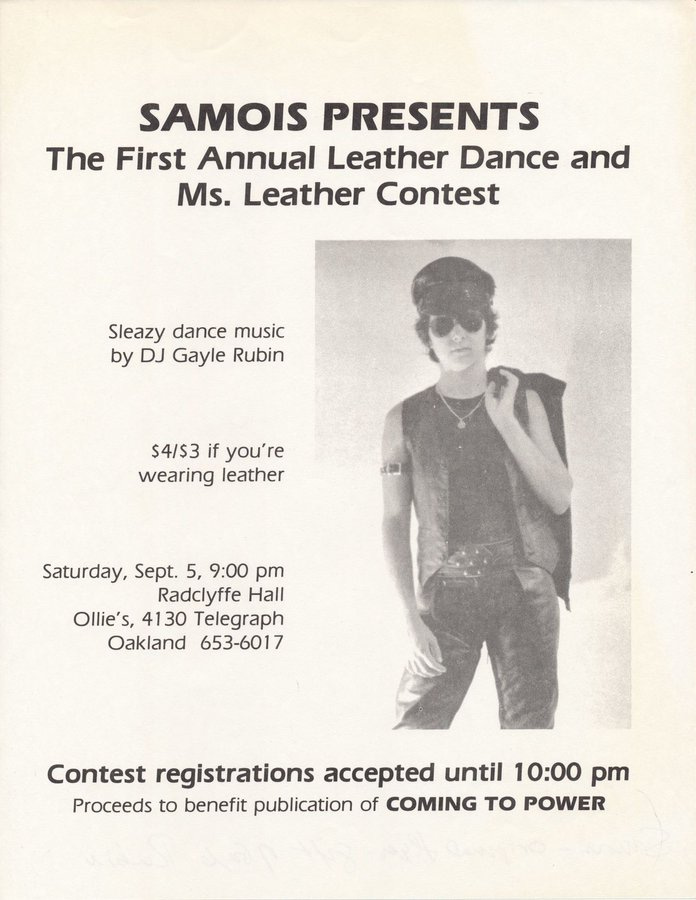

An anti-anti-porn faction began to take shape, articulating a sense that feminist anti-porn activism was in fact puritanical and at odds with sexual liberation. In San Francisco, the leather capital of America, a group of lesbians founded the Samois, the first lesbian BDSM organization in the U.S, in 1978. Pat Califia and Gayle Rubin were among its founding members. WAVPM and the Samois existed in direct opposition to each other, and indeed sometimes picketed each other; the conflict between these two groups was one origin point of what would be termed the Feminist Sex Wars.

It’s worth diving a bit into what, exactly, each of these camps stood for. (I’m drawing heavily here on Lorna Bracewell’s book Who Lost the Sex Wars?, which I found incredibly helpful and insightful - highly recommend if you are interested in going deeper on this stuff.) Though they are often presented as stark opposites, these two camps did share some common commitments. Both sides were interested in interrogating the politics of sex and sexuality, insisting that these were not merely personal or private areas of life but aspects of a social terrain on which political battles were fought. Both drew heavily on lesbian feminist political thought and practice, and both were highly critical of normative heterosexuality. And, though the Sex Wars are often presented as a conflict between sets of white feminists, both camps contained significant numbers of feminists of color who incorporated anti-racist critique into their arguments about sexual expression.

Though their politics shared these elements, the political arguments presented by anti-porn feminists and sex-radical feminists were certainly in conflict, and their ideas about how feminism should approach issues around sexuality were incompatible. Anti-porn feminists primarily argued that pornography and sexualized depictions of violence against women (and sexual practices that incorporated violence, such as BDSM) normalized the objectification of women. Beyond that, they saw porn as a sort of propaganda for the hetero-patriarchal agenda, conditioning both men and women to accept a caste-like sex system. Additionally, anti-pornography feminists of color argued that porn normalized and promoted sexualized racist stereotypes of both men and women of color, and made solidarity between men and women of color more difficult. Anti-porn feminism took as its starting point that sexual violence and other forms of violence against women were rampant, and that vectors through which the objectification and degradation of women were promoted should be stopped.

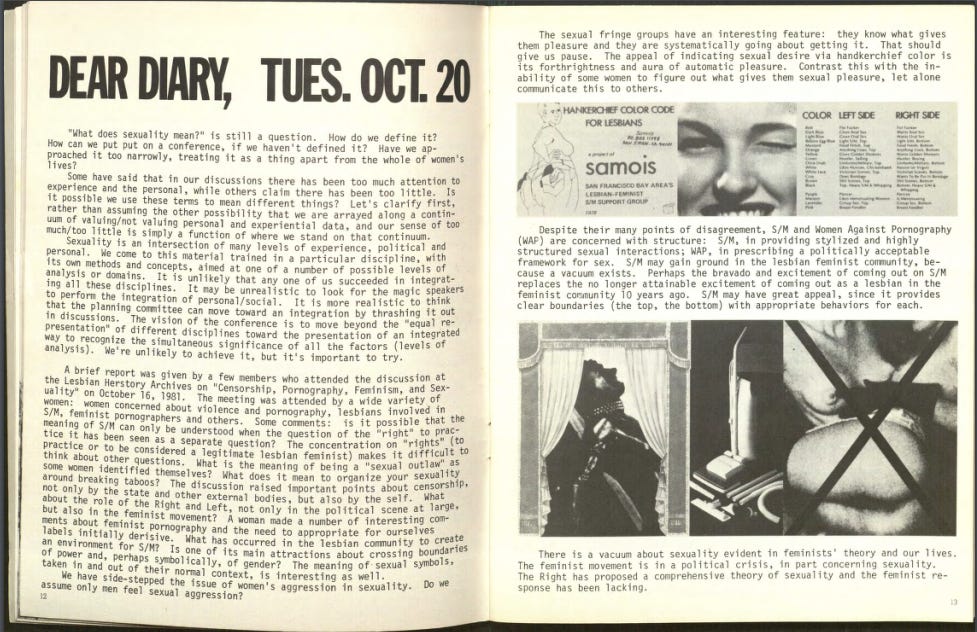

Sex-radical feminists, by contrast, saw sexual practices outside of heterosexual procreative sex as universally marginalized, with that marginalization intensifying the further away you got from that normative center - what Gayle Rubin termed the “charmed circle.” These feminists were interested in claiming sex as a liberatory practice, a space in which the desires of women and queer people could finally be expressed. Sex-radical feminists were interested in interrogating all forms of sexual taboo, including, in some cases, incest and pedophilia/pederasty. To be clear, their arguments were not that these practices should be straight-up accepted and embraced, but rather that a sexual value system that arose out of patriarchal strictures could not be trusted, and must be reexamined across the board. This did not necessarily mean that they saw sexuality as a free-for-all; for example, in What Color is Your Handkerchief? A Lesbian S/M Sexuality Reader, Barbara Ruth argues that S&M should never be practiced between heterosexual partners, only members “of the same sexual caste.” Bottom line, feminists of this group were determined to develop a radical feminist approach to sexual liberation.

Tensions rose through the last years of the 70s and into the new decade. Ellen Willis’s 1981 essay, titled “Lust Horizons: Is the Feminist Movement Pro-Sex?,” expresses dismay with the state of the discourse. While ultimately allied with the goal of sexual liberation, she has skepticism for both the anti-porn and sex-radical sides of the conflict. She finds it “disconcerting” that “feminists are as confused, divided, and dogmatic about sex as everyone else.” The anti-porn feminists were overly dogmatic and conservative in her estimation, while the sex-radical feminists seemed unwilling or unable to do any sort of deeper unpacking of the embedded meanings of S&M fantasies. Judgement and refusal to judge had both become stultifying dogmas. It is time to “get a grip,” she writes. This would start with a willingness to revisit hardened beliefs, she proposed: “Women’s sexual experience is diverse and often contradictory. Women’s sexual feelings have been stifled and distorted not only by men and men’s ideas but by our own desperate strategies for living in and with a sexist, sexually repressive culture. Our most passionate convictions about sex do not necessarily reflect our real desires…If feminist theory is to be truly based in the reality of women’s lives, feminists must examine their professed beliefs and feelings with as much skepticism as they apply to male pronouncements.”

In 1982, the year after Willis published her essay, Barnard College held its annual feminist conference, with sexuality as its theme. Willis and Gayle Rubin were among its organizers, and the conference was openly geared toward a pro-kink, -taboo, and -porn direction. Its organizers stated that their goal was to expand the feminist discourse around sexuality, to examine its possibilities not just as a site of danger, but at a site of radical pleasure. In the lead-up to the conference, women from the group Women Against Pornography began bombarding the college with calls and letters protesting the conference. At the last minute, college officials confiscated 1,500 copies of a text the conference planners had assembled called Diary of a Conference on Sexuality, which contained planning minutes, notes from organizers, erotic collages, and a schedule of sessions. The entire booklet can be found online here, and I highly recommend checking it out - it’s fucking cool. The planners were clearly unafraid of courting controversy; the opening letter of the Diary, penned by conference chair Carole S. Vance, asks, “What are the points of similarity and difference between feminist analysis of pornography, incest, and male and female sexual “nature” and those of the right wing?” The question thinly veils its indictment of the anti-pornography feminist wing as hopelessly conservative.

Though the college hedged on its support of the conference, the show went on, with WAP protesters picketing outside, wearing shirts emblazoned with the slogan “Against S/M.” Picketers distributed leaflets speculating on the specific sex practices of conference contributors such as Dorothy Allison. Meanwhile, the actual work that took place within the conference’s sessions was diverse, ranging from a session on fat positivity to a class analysis of psychotherapy. The boiled-down version of the conflict (porn: yea or nay?) belied a much broader and complex set of political interests on each “side,” some of which, as I’ve mentioned, were overlapping.

Conventional wisdom holds that the pro-sex faction ultimately won the war. After all, by the aughts, “sex positivity” was a ubiquitous feminist buzzword, and, within most feminist spaces, a blanket rejection of pornography, BDSM, or sex work would be seen as retrograde (though, of course, phobia toward sex workers remains rampant, and many feminists fall far short of advocating for fully legalized sex work). This view is oversimplified, however. In her book Who Lost the Sex Wars?, Lorna Bracewell argues that the sex wars should be understood as a conflict not just between anti-pornography and sex-radical feminists, but rather a triangular struggle between anti-pornography feminists, sex-radical feminists, and liberals. (It’s worth noting that her usage of “liberal” is drawn from the political science definition, not the colloquial one - she uses the term to refer to an ideology of individual freedom that divides a public sphere, mediated by law, from a private one, which should remain untouched by law.) Anti-pornography and sex-radical feminists alike were positioned in opposition to liberal power, as both camps insisted on politicizing sexuality and sexual expression, which liberalism would relegate to the private, de-politicized realm. Bracewell argues that, over the course of the 1980s, there was a creeping liberal capture of ideas and, in some cases, alliances, from both sides of the feminist conflict. Many of the most wide-spread contemporary feminist approaches to sexuality, Bracewell argues, can be traced to these moments of liberal capture, including #MeToo, SlutWalks, and trigger warnings.

The politics and events of the Sex Wars continue to shape feminist and queer ideas about sexuality and sexual practices, not least on Lex. Before we go, we’ll turn to two publications from opposite sides of the Sex Wars, both emblematic of their movements - and one of which served as the original inspiration for Lex. The first of these was a paper called off our backs, founded in 1970. Small-scale DIY magazines, papers, and newsletters were the lifeblood of the lesbian feminist and radical feminist movements in the 70s - significant among these were The Lesbian Tide, The Lesbian Connection, Sinister Wisdom, Big Mama Rag, Sojourner, and off our backs, among many others. oob was politically aligned with the anti-porn feminists, and published many of their writings. off our backs, of course, was not only focused on anti-porn organizing. A sample issue from 1976 includes an interview with Assata Shakur; several updates on anti-carceral organizing efforts, including an article about ongoing legal developments in the legal case of Joan Little, a woman charged with first degree murder for fighting back against her rapist; an article about the meeting of the Coalition of Labor Union Women; an article protesting the abductions of Native American children by the state; multiple pieces each about welfare issues and women’s health issues, including safety issues with tampons in the US and forced sterilization in India; and film reviews, classifieds, and poetry. This was a few years before the Sex Wars reached their fever pitch and later issues would feature anti-porn writings more prominently (1976 was the last available year I could access on Jstor, lol) but my point is that anti-porn organizing existed as one issue amongst this larger political web.

In 1984, a group of lesbians in San Francisco published the inaugural issue of On Our Backs, the first by-women-for-women lesbian erotica magazine. Its name, of course, was a cheeky jab at oob, and it did not go unnoticed; off our backs published criticism of On Our Backs as “pseudo-feminist” and threatened legal action over the new magazine’s logo. If off our backs was emblematic of the style and ethos of the lesbian-feminist 1970s, with its cut-and-paste look and fierce political stances, On Our Backs became emblematic of a 1980s lesbian eroticism, foregrounding fun, sexiness, and provocation.

None of this is to say that On Our Backs was without a politics! The magazine proposed that sexual pleasure could and should be a feminist pursuit by providing a stage for all sorts of lesbian desires, kinky and vanilla alike. There’s a great history of the making of OOB here, with lots of fab pictures and primary sources - check it out.

This brings us to the On Our Backs personals section. Each magazine featured personal ads sent in from lesbians across the country seeking sex and/or love. OOB was a welcoming place in which to advertise all sorts of lesbian desires, and women did, as the roundup below (sourced from Instagram, hence the formatting) makes clear. If you are a Lex user (pre redesign), the formatting and typeface should look familiar….

So this is where I will leave us for today; with the personals ads published in a vibey lesbian erotica magazine that was named to refute/piss off an older (also vibey) lesbian political newspaper, which documented one side of a pitched political battle over porn, violence, and sexual expression, which emerged out of lesbian tradition of asking big questions and fighting big fights….and in the next newsletter, we will see how Lex aimed to carry forward a little piece of this legacy, and think about how it’s all turned out! Love you xo

This is the first time I’ve read this newsletter. I love this! I love all the archival links! And can’t wait to read the other two parts / everything else. Subscribed.