At the end of the first part of my series about Lex, we became acquainted with the 80s lesbian erotica magazine On Our Backs, which was home to a legendary personals section frequented by all sorts of dykes looking to suck and fuck. Smash cut to three and a half decades later; the year is 2018. Covid is still just a twinkle in the devil’s butthole, the “orange man” is “president,” and lesbians, if you can believe it, are still looking to suck and fuck.

In 2018, I myself was fresh off a devastating breakup that shattered my world, and was single for the first time since I was a teenager. Despite the fact that I now lived in a tiny room that could only fit a monastic twin bed and was still getting into crying fights with my ex-girlfriend on a weekly basis, I decided to try online dating for the first time. Alongside the regular culprits (Tinder, Hinge) there was also Personals, an account on Instagram that posted personal ads from lesbians and lesbian-adjacents all over the world, founded a year earlier.

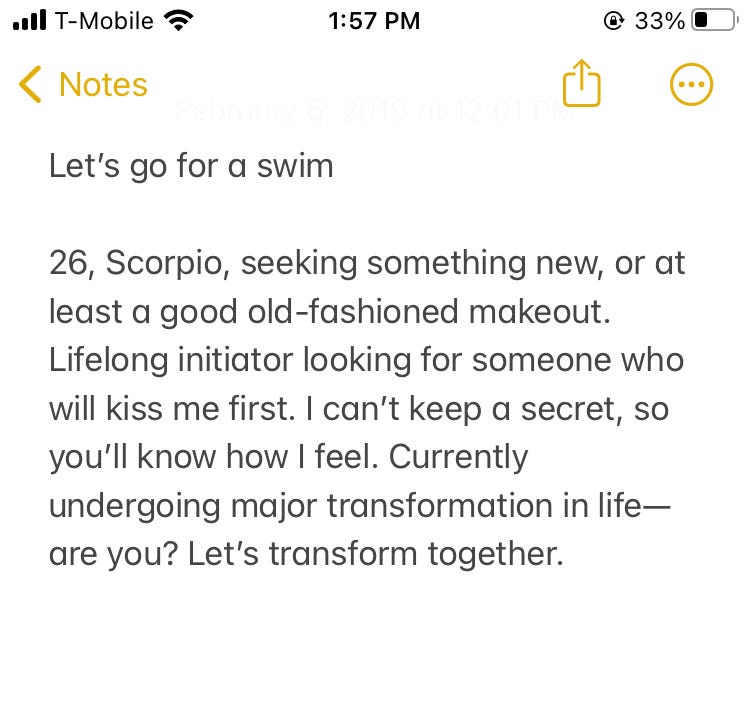

Personals was honestly kind of thrilling. Each day, they posted a fresh batch of ads, each one containing a block of text on a turquoise background, with the poster’s Instagram handle and geographic location tagged in the caption. I scrolled their new ads every day, not infrequently spotting friends and acquaintances in the mix. There were lots of posts from New York, L.A, and the Bay Area, yes, but also from everywhere else. I scanned for the Philly ads; I shot my shot. I went on sweet dates with a musician and a college student; I had my first kiss post-breakup and then my first sex. I labored over my own ad, drafting it in my Notes App and sending it to friends for revisions before submitting it to be posted.

I fell into a relationship with someone I met on Tinder; together we practiced a cursed form of polyamory in which I basically did not date. News circulated that the Personals people were developing a lesbian dating app, which excited me greatly. My then partner and I broke up one month into pandemic lockdown. Shattered again. As spring warmed into summer, a new mood overtook me. That mood was horny.

By this time, Lex was up and running. I logged on from the Harvard-owned Victorian mansion in which I was quarantining alone (a tale for another time). Let me tell you, friends, the vibe on Boston Lex that summer was HORNY INDEED. I remember lying in a bathtub of cool water in the heat of July, posting a solicitously flirty ad on which I had basically no intention of following through, and raking in the thirsty responses. Scrolling through the local posts, everyone was was dying for it. That summer I messaged fellow Lex users about pod sizes and days in isolation and possible exposures. I had sweaty sex with a small handful of strangers I never saw again, which seemed to me a form of necessary recklessness, resetting a clock inside my body that counted down to the moment at which I would vibrate out of my own skin and fall apart forever. The loneliness of those months, as you may also recall, was crushing.

As winter set in, the Lex vibe shift was swift and unsubtle. The unabashed lust that had infused the app in the summer was replaced by angst. Everyone on the app was sad, or angry, or lonely, sadly horny, or angrily sad, or hornily lonely. This is when I came to see Lex as I see it now: a singular mix of lesbian Craigslist, public diary, community PSA/chastisement message board, and yes, sort-of dating app, albeit one where you can’t get a good look at anyone and are really unlikely to get laid.

The design of Lex has a lot to do with this, and it was a design born out of an interest in how lesbians navigated sex and dating in the past. The creator of Personals and founder/CEO of Lex, Kell Rakowski, has recounted her tale in interviews for articles like this. She stumbled across the On Our Backs personals ads when looking for things to post on her lesbian history Instagram account, @h_e_r_s_t_o_r_y. She created the account when she was first coming out as gay, struggling to find queer connection while still existing in a straight social world. Inspired by the sexiness and wit of the OOB ads, she created her own Personals account, and, when its popularity became overwhelming, she began to develop the app.

In light of this story, Personals held an almost utopian appeal, for both Rakowski and future users. First, it was a way, in the midst of the loneliness and isolation that marks queer existence for many, to be lifted into connection both with other lesbians who might date you and with lesbians of the past, with whom you could find resonance and context for your own life. The sexual frisson of it all existed both in the tie between present-day writer and reader and the tie between present-day dykes and dykes of the past.

Second, through their text-only format, Personals and then Lex offered a utopian lesbian theory of attraction. Both were designed to minimize the image, instead foregrounding only text. Both Personals and Lex offered a route to see images of the people you were interacting with; Personals posts all linked to the writer’s Instagram account, while Lex offers the option for users to link their Instas, and, due to demand, eventually built in the option for users to add a single image to their profile. However, in both cases, the way you encounter another user is not, as in most dating apps, first through a picture of their face or body, but rather through a text post. This is, I think, pretty easily understood as a reaction to the brutality of dating-app culture, in which it is easy to feel that your appearance is constantly judged and rejected by others. Here, the app suggests, others will experience you first by your words, their attraction sparked by what you say and not by your hot bod.

The text-forward format echoes the outdated but persistent notion that women experience attraction less visually than men. Of course, this is a weird gender-essentialist idea that I’m sure Rakowski/the Lex team would never claim. There’s an aspirational quality to the text-forward concept though, that bends toward the “women” side of that equation, as gay male-centric apps like Grindr bend toward the “men” side, by allowing users to exchange in-app dick pics and such. And it is aspiration, because the vast majority of people experience attraction as being fundamentally threaded through the visual and physical dimensions of the body, as well as intangible emotional, intellectual, and energetic factors. Many users, including myself, ultimately do want to see what somebody looks like before agreeing to go on a date with them, especially when the date is prompted by an ad in which the other person is begging to be choked out. And, perhaps just as importantly, I want them to see what I look like too! Because, of course, the body really can’t be secondary to the spirit when it comes to attraction, at least most of the time.

That being said, we do exist in the world, and so abstract arguments about the failings of mind-body dualism aren’t the be-all and end-all of online dating. It’s well documented that fatphobia, transphobia, racism, and ablism are all reflected in people’s dating app habits, and it’s tempting to imagine that some of this bigotry could be checked by burying people’s pictures behind multiple clicks and introducing them to each other with disembodied text first. But my point, I guess, is that most people want to date and fuck people who are attracted to their actual bodies and actually would rather screen out potential dates who will think than they are too fat, or who don’t want to date a trans person, or who are white supremacists, hence (in part) why so many Personals and Lex ads list these identity signifiers in-text.

This brings us back to the inspirational source material for Personals, because people did indeed meet and have sex and fall in love by meeting through text-only personals ads printed in On Our Backs and lots of other places. I think what's missing, though, in translating that format into the online present, is that OOB personals were produced by the constraints of their moment. Any print periodical has to contend with the costs of paper, printing, and mailing. Personal ads in OOB and elsewhere were text-only because that was the only way for them to work on an economic level. And indeed, many ads asked respondents to include a picture with their letter! In the context of online spaces where images are ubiquitous and cheap, the absence of images on a dating app is an interesting provocation, but it doesn’t make for sustained use. It imagines us as we might be, not as we are. Lex proposed that lesbian online dating might be both post-photo and pre-photo, but the truth is we’re peak photo.

There’s another layer of embedded aspiration that I think is present in Lex’s design, and this is in how it conjures Sex Wars-era kink. Personals and the original design of Lex both openly referenced the typeface, color scheme, and layout of the OOB personals, and it’s been a talking point for Rakowski in interviews. Though users surely ranged widely in their awareness of this reference point, it’s something that deeply colored the development of the app and its use. I want to argue that, by placing its users on an updated OOB personals page, Lex signaled that the debates of the Sex Wars about sexual ethics and sexual violence and kink and relational values were done, and that the pro-kink side won. Plus, it suggested that we, the enlightened lesbians of the twenty-first century, would have all been amongst the playful kinksters. We would have known which side was right.

Well, spend five minutes scrolling on Lex, and you’ll see that this is NOT the case. The irony of Lex is that it offered a nostalgic reprise of a historical Sex Wars-era format that gave the illusion of a settled historical debate, and in that new space a Sex Wars redux exploded. Indeed, though horny-posting has endured on Lex, alongside a host of what can only be called Lesbian Craigslist posts searching for roommates and selling scam concert tickets and the like, Lex has also revived a tradition that’s a lot more reminiscent of off our backs than On Our Backs. Namely, a whole lot of people use it as a space to editorialize, deliver public service announcements, scold fellow queers, beseech the community, howl at the moon in joy about the beauty of gay love, call people Nazis for not wearing masks (this is a real example), and so forth. These are not personal ads, really. Rather, they are straight out of lesbian newsletter reader letter bag!!

Lesbian feminist newsletters, for a bit of background, generally had a willingness to publish reader response letters, often about articles in previous issues and community events, expressing a wide range of disagreements and perspectives. These were basically analogue message boards, where lesbians hashed out community debates, sometimes quite acrimoniously. I am using such newsletters as sources in my dissertation and I find a lot to admire in how these dykes valued dialogue and the right to disagree. What Lex reminds me of is how annoying it is to watch this stuff play out in real time, especially when some people express their disagreement by claiming that, in fact, anyone who disagrees with them is evil. As it was then, so it is now.

Below are a few clips from the off our backs letters section, from 1972-74. This is just a tiny taste, but I tried to capture the breadth of what was published there, from letters praising the magazine to scathing criticism to women searching for local feminist community to a woman writing from prison asking for support.

The wet n’ windswept face of lesbianism conjured by spaces like the On Our Backs personals is an illusion, and it was an illusion at the time too. When you’re writing an ad of limited length and paying to have it published in the hopes of getting railed, of course you will put your sexiest, most alluring face first. (This is, by the way, is why the vibe on Personals was so different from the vibe on Lex - more on that in my final installment.) It’s a personal ad - an advertisement, with yourself as the product. But in the slushy mix of the reader response mailbag, all that sexiness and polish is out the window. It’s just a whole bunch of dykes and their gripes.

It’s notable, too, that Lex has become a space where people specifically hash out different viewpoints about sexual and romantic ethics: the stuff of the Sex Wars. The specifics of the debates are different, of course; I haven’t seen anyone on Lex argue that pornography should be made illegal, although I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s happened. But people constantly complain that the space is too horny or not horny enough; that everyone is too monogamous or too polyamorous; that people are objectifying femmes; that people’s Covid protocols are wrong; that sex and love are, abidingly, too hard to come by, and it’s because other people do things the wrong way.

More specifically, it’s become a space where trans politics get litigated. Time and again, users (including non-binary users) will post they are seeking AFAB dates or roommates or whatever, sometimes invoking language of safety, leading to posts rightful criticizing this TERF-adjacent understanding of gender. Meanwhile, I have heard anecdotally that trans women are more likely to get reported or banned. The app, too, had an original policy of welcoming only queer people who were not cis men as users, which was confusingly presented and impossible to enforce, with a strong likelihood of transfem people being wrongfully booted. Posts criticizing this policy were abundant, and it has since been changed, though there were and are also plenty of posts complaining that the app is overrun by cis men (something that, to be honest, I’ve never seen evidence of, though it’s hard to assess on a wide scale).

We are not the breezy, sexy kinksters conjured by the OOB personals and we never were. Lex seems to know this, as they’ve redesigned the app (“Green Lex”) and rebranded as a vague queer community app; their new slogan is “If it’s queer, it’s here.” And it is, at least some of it: the crankiness, the corniness, the horniness, the loneliness, the dreaminess, the earnestness, the humor, the bad poems.

As I wrap up this newsletter, I am feeling self-conscious. I’m afraid that I will come off as too negative, which, on the lesbian internet, is kind of a no-no. My goal is not to tear Lex to pieces; I’ve had good things come from using it! But I feel (and many of those of you who wrote to me feel) that its original concept offered a promise that it didn’t, or couldn’t deliver, and that this was a disappointment. What I’m interested in, then, is probing that disappointment, and that is what I’ve tried to do.

The next and final installment of my newsletter will be a tour of some of Lex’s very distinctive norms and cultures: the weird, the wild, the funny, the depressing, the sweet, and the off-putting (lol). I will share some of what you all wrote in to me, and there WILL be screenshots. Thanks for reading <3

wow, this one really took me on a ride. memoir, history, analysis; it has it all. a fucking great read, and actually works at synthesizing some of the big mess that is Lex. the cruising spot vs the newsletter...two sides of the same lesbian coin...

i love your description of lex as having utopian aspirations, and the reality of it, which is “It imagines us as we might be, not as we are.” super accurate, i think.

also, wanted to note that i’m reading this in the bouldering gym, which i think is some sort of lesbian praxis in and of itself