Hello, friends and comrades. Wow, seasonal depression and the increased workload that comes with teaching this semester have really kicked my ass the last month or so. Luckily, the days are getting longer and I’m feeling better adjusted to my busier schedule. I’m currently staying with my parents in the Boston area so I can TA at Harvard, and so I’m away from my precious South Philly house and beloved friends and roommates there (hi, if you’re reading this!).

A couple weeks ago, I drove with my mom and dad to Rochester to pack up my grandparents’ beautiful house, which I wrote about here. They hated to waste anything and so do we, and so we’ve done our best to find homes for all their things, and it’s been LOT of work. We also brought a whole bunch of stuff back, including thirteen (THIRTEEN!) boxes of old photographs taken by my grandfather. I’m inheriting a bunch of posters, paintings, ceramics, stained glass, and more, and I’m so looking forward to incorporating all those items into my own home when I get back to Philly. As I wrote about in the piece linked above, their cozy, artful, tchotchke-filled house has thoroughly shaped my aesthetic sensibility when it comes to interiors. Sadly, the center pane of a large stained-glass panel that I am so excited to inherit broke in transit; I blame a combination of my own insufficient bubblewrapping job and hastiness on the part of the movers who loaded the truck. I should be able to get it repaired. It may not look the exact same as before, but hopefully it will still be beautiful.

Speaking of beauty, today I’m going to use this newsletter to think through some thoughts about beauty, the beauty industry, bodies, and feminism. Over the last few weeks, I read through a whole bunch of the archives of

, a newsletter by the beauty industry critic Jessica DeFino. Her writing has really been challenging me to think in new ways about my relationship to beauty culture. It’s easy for me to tell myself that I exist outside of mainstream beauty culture, which is generally so straight-coded. This is, of course, totally untrue. Not only do various types of beauty-related marketing get to me all the time, but the more existential messages of beauty culture are sunk deep in my psyche: being beautiful is being happy. Everyone wants (and should want) to be beautiful. To be beautiful, you must curate and alter your appearance. Beauty requires work that can never be done.DeFino’s stance on this stuff is unyielding in a way that I really respect. She argues that most commercialized skin-care is a complete scam that actually decreases your skin’s ability to self-regulate, creating a set of problems that you can then be sold more products to regulate. She writes about the sick relationship between the beauty industry and the fossil fuel industry. She cuts through the bullshit rhetoric around celebrity plastic surgery.

She’s also written about the concept of the unmodified body, and interviewed Clare Chambers, a philosopher who wrote a book about this idea called Intact. I haven’t read the book, but I’ve read a few interviews with Chambers. Basically, what she’s proposing is not a celebration of bodies that have not in any way been modified (which would be impossible - clipping your nails is modifying your body, eating food is modifying your body…) but rather a political principle designed to resist the coercion to modify. I chafed a bit against this principle when first encountering it, for transfeminism-related reasons; after all, as I’ve touched on here before, feminist rhetoric idealizing naturalness, particularly when it comes to bodies, can go to transphobic places real quick.

However, I don’t think this is quite what the concept of “the unmodified body” is up to (although I’m still not totally sold on the use of the word “unmodified” for this purpose). The key idea here, to me, is a resistant stance toward coerced modification and the framing of beauty and diet cultures as coercive forces. Indeed, put in this framework, we can see that trans people are strongly coerced not to modify their bodies (and any pressure that they experience to modify can’t be understood as existing separately from the massive pressure on all of us to be cis, or as close to it as possible).

All of us are coerced to modify our bodies all the time, whether to be more beautiful, more thin, more gender normative, less disabled, and so on. What’s interesting to me is that it feels like there’s no way to talk about the particular pressures of beauty culture, at the current feminist juncture we find ourselves at, without seeming really obvious and dorky. (DeFino’s writing does not feel obvious or dorky to me, by the way, which is why I’m impressed by it.) There has been such total capture of this issue by liberal/capitalist feminism and it’s completely deadened critique. Railing against beauty culture is out of fashion; it’s giving Naomi Wolf. Beauty and skincare industries have fully commodified “self-care” language, which most of us who are fluent in sensibilities of the left are inclined to dismiss with an eye-roll, but that dismissal itself is an act of permissiveness. And what that permissiveness enables is the invisiblization of the the reality that beauty culture, entwined with diet culture, is a structural coercive force that causes us all to suffer.

Diluted “personal choice” feminism, again, can be pretty easy to spot and dismiss on a case-by-case basis, but I really do believe that it has narrowed the collective feminist imagination in devastating ways. (Maybe somebody has already written about this, but it seems like the feminist “personal choice” ideology developed and became dominant as a way to resolve entrenched feminist disputes, like the sex wars, and it solved nothing and now we’re fucking stuck with it? Thoughts?) Anyway, wear makeup or don’t, get fillers if you must, whatever, but the point is that nobody makes a choice to do this stuff that isn’t shaped by the grinding machinery of an industry that makes bank off of enforcing people’s unhappy relationships with their (aging) bodies. Again, I am well aware that this is such an obvious take, but still…

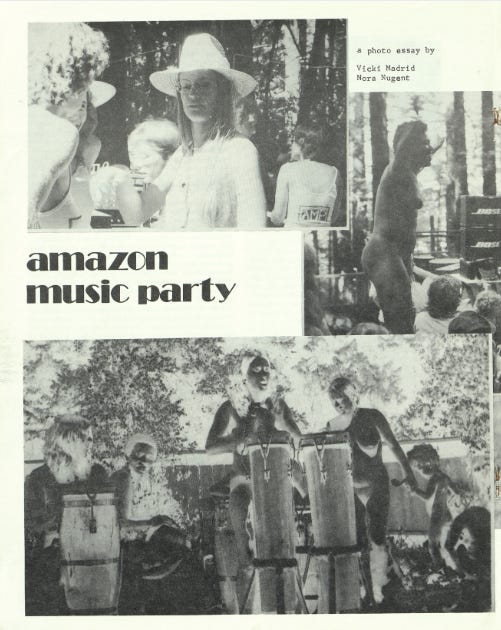

As usual, I am brought to mind of the complex legacy of 1970s lesbian feminism, and the lessons that it might continue to teach us, if we are willing to listen. While reading old lesbian feminist mags for my research, I came across this page from a 1974 issue of The Lesbian Tide:

Something about the ecstatic nature of this photo spread really touched me, particularly the picture of the nude woman standing with her arms raised on the first page. The forest, the flute, the feeling of air on skin. The aesthetics of 1970s lesbian feminism are really on display here: earthy, androgynous clothing, no makeup, shaggy haircuts, tits out, etc. These dykes rejected many of the inherent standards of hegemonic beauty culture, but of course they also created their own exacting ideals that could sometimes be oppressive or alienating. But what these images bring me back to is that a rejection of beauty and diet cultures can also be a commitment to bodily pleasure, to embodied joy. I feel most ecstatic in my nude body when swimming naked, ideally in a pond at night. In those moments, my body is pure sensation, and how I look ceases to exist. We lose sight all too easily of how the pressure of eyes on our bodies (our own eyes, the eyes of others, our own eyes imitating the eyes of others…) can foreclose types of feeling. I don’t think it’s possible to feel ecstatic and to be managing how one is perceived at the same time.

In a personal essay, DeFino writes about her eyebrows. She has trichotillomania, a condition that causes her to compulsively tug out her eyebrow hairs, and getting her eyebrows microbladed is one of the few beauty rituals she has held onto. She writes in this essay about deciding to skip microblading for the first time, because it would mean she wouldn’t be able to go swimming for a week, a beloved daily ritual. She writes: “Do I love the way I look? No. Do I think I look beautiful? Also no. But those are not my goals anymore, and so not meeting them isn’t upsetting. It’s whatever. I’d rather read a book on the beach than get microblading. I’d rather feel the ocean on my face than feel beautiful.”

This is the energy I’m trying to bring to my own life, currently. Pleasure and beauty don’t always conflict, but when they do: pleasure over beauty, every time.