Hi freaks. Today I am sharing a historical dispatch from the Grand Lesbian Tradition of DIY, Construction Projects, and Interior Design - Lesbian Interiors, for short. My investment in this subject is twofold: first, I’m interested in thinking about how built spaces, often renovated in a DIY fashion for both financial and ideological reasons, were so integral to the functioning and vibe of lesbian feminism in the era I study (late 1960s-80s, roughly); and second, I myself am a dyke in the process of renovating a home and am very much reliant in this process on various queers in my life. Lineage vibes! I’m definitely not alone in my interest in the history of lesbian interiors - see, for instance, the below post celebrating the wonders of dyke handiness, shared by

.This newsletter was inspired by a photo by Joan Byron, AKA JEB, the great photographer of lesbian and queer culture over the last half-century. Her pictures are iconic for a reason! She is incredible at capturing lesbian connection and love, and her photographs almost always center lesbians and their loved ones, often in relaxed intimate moments. At the edges of these pictures, and just as interesting to me, are the environments that these lesbians and their communities built and furnished.

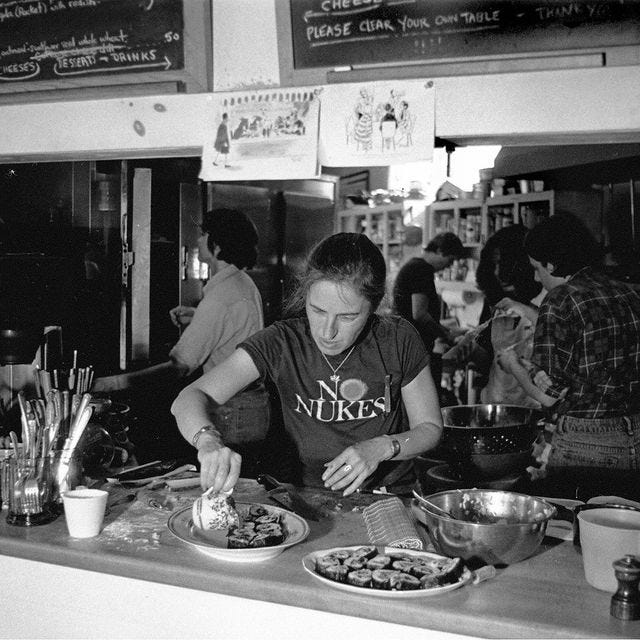

This is a picture of Selma Miriam, one of the co-founders of Bloodroot, a vegetarian feminist restaurant in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Bloodroot opened in 1977, when women were opening feminist restaurants (as well as cafes, bookstores, bars…) in cities across the U.S. in large numbers. A “feminist” restaurant could mean that it employed only women, that the restaurant was heavily engaged in politics related to feminism (see the “No Nukes” shirt pictured here - feminist anti-nuclear organizing was a BIG thing that I plan to write about further!), that the space hosted women’s groups and events, or in some cases that only women were welcome in the space.

Design and the built environment heavily were entwined with politics and values in places like Bloodroot. Unlike most feminist restaurants, Bloodroot is still open today (I actually first heard about this place from a friend who was stopping there on a road trip, hi Agnes!), and their website advertises how the restaurant’s communal and egalitarian values are expressed through its design: “There’s no cash register and no waitressing. Place your order with a woman seated behind a desk after making your choice from the blackboard menu. Enjoy your food either in our comfortable dining room or on our patio in good weather, and bus your own table when you are through.” I love the part about the desk - this system is all about disrupting the familiar relationship between service workers and customers, and (as anyone who has worked in the service industry will know) the layout of physical space in restaurants plays a large role in determining how people relate to each other. A desk implies expertise, authority, knowledge, and, on a practical level, it also means that the person working there can sit down.

This system of ordering, self-busing, etc. feels pretty similar to the systems of today’s *fast-casual* and cafe-style restaurants, but the underlying logics and ethics are completely different. So much of the design of fast-casual places and the like are about streamlining, aka eliminating the need for workers. These places also often have a vibe of soulless efficiency, one that actively curtails the possibility for human connection and encourages visitors to feel like customers purchasing a commodity, not as participants in a shared space. You often see employees absolutely scrambling, trying to keep up with flurries of Uber Eats orders AND keep up with prep AND manage the line AND keep the floor from descending into utter disarray. It’s always clear, in these situations, that the restaurant is experimenting with just how much labor it can squeeze out of a shrinking number of underpaid workers. Transferring some of the activities of service to customers (such as busing tables) is about tightening that squeeze, and actually heightens the inequality between employee and customer. The fact that Bloodroot uses these same mechanisms in service of a consciously egalitarian ethos is really interesting to me, and goes to show that economic goals, ideological commitments, and the arrangement of physical space can be aligned in radically different ways even within seemingly similar setups.

Some of Bloodroot’s politics are expressed in very literal ways in the space. There’s a hand-written sign, hung there since early days, stating: “Because all women are victims of fat oppression, and out of respect for women of size, we appreciate your refraining from agonizing aloud over the calorie count in our food.” This is so charming to me, in the way that it anticipates and shuts down a specific set of oppressive behaviors while also encouraging customers to reflect on anti-fat bias.

Bloodroot’s egalitarian values are visible, too, in JEB’s picture above. The open kitchen eliminates boundaries between staff and customer, making the working practices of the restaurant visible to all who walk through the door. The interior of the kitchen hews more closely to co-op kitchens than to restaurant kitchens I have know, with its dry goods stacked on cubby shelves, utensils casually stored in a jar, and hubbub of dirtied metal bowls and dykes in flannels.

The dining room is also clearly designed to echo a home-like space, with mismatched wooden furniture, armchairs, bookshelves, and walls completely covered with art. There’s a clear emphasis on “natural” materials here - materials like wood and woven textiles that are both derived from plant materials and carry cultural connotations of traditional old-timiness. The textiles hanging from the rafters really stand out to me - there’s an emphasis here on feminized craft traditions that really carries the whiff of 1970s feminism to me, with its emphasis on recuperating histories of women’s work and forging (and celebrating) a connection between womanhood and nature.

This really great article by Maria McGrath titled “Living Feminist: the Liberation and Limits of Countercultural Business and Radical Lesbian Ethics at Bloodroot Restaurant” chronicles the history of the restaurant, and McGrath points out how the owners of Bloodroot were aligned with feminist theorists like Mary Daly who promoted bio-essentialist notions of womanhood based in traditions of healing, mothering, and environmental connection. (McGrath contrasts this, helpfully, to Shulamith Firestone’s proposal that women could be liberated by hypothetical reproductive technologies that could take care of gestation, unlinking women from a sex class system tat relegated them to reproductive labor.) Sadly, I also learned from McGrath’s article that Selma Miriam and Noel Furie, the two remaining cofounders of the restaurant, have made anti-trans comments in more recent decades. In 2018, there was an online conflict that originated when a customer posted on Facebook about being upset by some awful comments made by the cofounders during a conversation at the restaurant. The customer and the cofounders describe this conversation in very different terms, and I obviously can’t speak to what “really happened,” but regardless, it seems clear that Miriam and Furie fall far short of being trans inclusive in their understandings of feminism and womanhood.

This obviously really fucking sucks, and also is not so surprising. Heavy investment in the “naturalness” of sex/gender roles leads to dark places. Obviously, I’m not suggesting that the presence of tapestries and quilts automatically means a TERF is afoot! (Disclaimer: I am currently making a quilt lol.) But it is interesting to me to see how these complicated feminist histories are enduringly threaded through physical spaces - and makes me wonder about the how we might inhabit and reappropriate these spaces and histories, differently, in the present.

As McGrath chronicles, Bloodroot emerged out of radical feminist and 1960s hippie/counterculture settings, and as its founding context transformed and largely faded away, the restaurant has had to transform its sense of purpose. Over the decades, the cuisine has evolved to include a more multicultural vegetarian cuisine, and the politics of the restaurant have become more focused on animal rights. There’s been a dramatic decrease in community events and feminist talks like the ones that it frequently held in its early years, with figures like Audre Lorde, Mary Daly, Adrienne Rich, and Rita Mae Brown coming in for events and meals. Atlas Obscura has an entry on Bloodroot that positions it, not wrongly, as a “last stalwart of the now-forgotten feminist restaurant movement,” a sort of museum of a bygone cultural and political era. It’s not a museum, though; it’s a persistent lesbian space that marks the enduring nature of the best and the worst of 1970s feminist politics, fifty years later.