Dykes Against the State, Part 1: Joan Little and Feminist Anti-Carceral Organizing in the 1970s

Free them all

An animating belief of my research is that the progress narrative most of us tend to reflexively believe when it comes to the evolution of LGBT and feminist communities is deeply incomplete and, in many cases, incorrect. What I am speaking about here is not so much the impact that gay liberation and feminist movements have had on society writ large (a very, very complicated topic beyond the purview of this blog post, lol) but rather the progress of the internal character of these movements. This progress narrative, which I have seen many of my former students bind to automatically, leads us to believe that movements of the past, though perhaps radical in their time, are problematic by the standards of today. We understand intersectionality; they (feminists, or whatever group, of the past) did not. Certain figures, like Audre Lorde or Angela Davis, become seen as solitary beacons of righteous critique. The fact that these women were operating within deep, broad, and diverse networks of activism and intellectual labor is easily erased.

The appeal of such a progress narrative is that it allows us to feel superior to many of the objects of our historical inquiry (while, again, reifying a few actors to an untouchable, God-like status). The type of intellectual gesture I am speaking of often includes a glancing use of the term “intersectionality,” as if the invocation of the term might adequately stand in for actual analysis of the particular workings of power and oppression in a given situation. This is an approach that inherently shuts down intellectual curiosity, for one thing. Another thing: these progress narratives are generally untrue, straight up.

I wrote in July about Susan Saxe, a lesbian leftist bank robber who was put on the FBI’s Most Wanted list and hid out in lesbian feminist enclaves. In researching her story, I felt moved to learn more about other U.S. lesbians and feminists who have fought to resist the state. I’m interested in this subject for…obvious reasons. We in the United States are living in the heart of a bloodthirsty and dying empire. Our attempts to resist often feel so, so small, and we are often separated by age, geography, social difference (not to mention prison walls, or death) from those who have resisted before. Some of those people have been lesbians and/or feminists, and as a *lesbian and feminist historian* of *lesbian and feminist history,* theirs are the stories I will explore here, keeping in mind that their work existed in conversation with all sorts of other people engaged in resistance.

While perusing various feminist newsletters for my dissertation research, I stumbled several times across the name Joan Little. (Note: Little’s first name is pronounced “Jo-ann,” and is variously spelled Joann or Joanne in some publications.) Little is a Black woman who was incarcerated in 1974 at 20 years old for burglary. At the North Carolina county jail where she was held, a white prison guard attempted to rape her while holding her at knifepoint with an ice pick. Little managed to seize the ice pick from the guard and stabbed him with it, delivering what turned out to be fatal wounds. Little fled the jail, and her rapist was found in her cell the next morning, pants around his ankles and semen on his leg. Little turned herself in to the authorities (as a fugitive, police were authorized to kill her onsite, so you can see why she made this decision) and pled self defense. The state charged her with first degree murder, a charge which carried mandatory death penalty in North Carolina if she was convicted. Her trial became a flashpoint in the national feminist movement, bringing together a diverse feminist coalition and pushing women in the movement to ask themselves what justice was really served by the criminal justice system.

Little’s legal defense team tapped into overlapping feminist and Black radical organizing networks to draw attention to her case, and the most high-profile Black women activists of the era spoke out on Little’s behalf: Angela Davis, Florence Kennedy, and Elaine Brown all spoke publicly about Little’s case, and Rosa Parks helped to found a Joan Little Defense Committee in Detroit.1 Bernice Johnson Reagon of Sweet Honey in the Rock recorded a song called “Joan Little,” featuring the lyrics, “she’s my sister, Joan Little…she’s your lover.” Davis published an article in Ms. Magazine titled “Joan Little and the Dialectics of Rape,” explaining how Little’s exposure to sexual violence in prison was not an isolated incident but endemic, and laying out how racial and gendered analysis were needed in tandem to understand Little’s situation. “In the Joan Little case, as well as in all other instances of sexual assault, it is essential to place the specific incident in its sociohistorical context,” Davis wrote. “For rape is not one-dimensional and homogeneous, but one feature that does remain constant is the overt and flagrant treatment of women, through rape, as property. Particular rape cases will then express different modes in which women are handled as property. Thus when a white man rapes a Black woman, the underlying meaning of this crime remains inaccessible if one is blind to the historical dimensions of the act.”2 The specific historical dimensions here being, of course, chattel slavery.

Thanks to successful fundraising efforts around the country, Little was released on bail while she awaited her trial (her bail was set at $115,000, or over half a million dollars today3). As historian Emily L. Thuma describes in her book All Our Trials: Prisons, Policing, and the Feminist Fight to End Violence, in the weeks leading up Little’s trial, a grassroots resistance movement brewed in the North Carolina Correctional Center for Women (NCCCW), where Little had been held before being bailed out. On June 15, 1975, nearly half the women in the facility began a sit-in in the courtyard, refusing orders to return to their dorms. The protesters pointed out that they had submitted tons of grievances regarding unsafe and unsanitary conditions in the prison, as well as racist comments made by prison staff and compulsory invasive pelvic exams that they had endured.4 On the outside, a local Raleigh group called Action for Forgotten Women (AFW), which organized in coalition with women prisoners, assembled to monitor the facility.

Over the following days, the sit-in escalated to a full-blown strike. Riot cops and state troopers were called in, and incarcerated women defended themselves with broomsticks and seized riot batons. Eventually, policed suppressed the protest using teargas and blunt weapons, sending dozens of prisoners into solitary confinement or temporarily transferring them to a nearby maximum-security men’s prison (an illegal action against which many of those transferred later brought a class action lawsuit5). Though the uprising was violently shut down, Little spoke publicly the following week about the terrible conditions at NCCCW, and women imprisoned there continued to speak publicly in the feminist press about their struggle.

Unsurprisingly, the movement to free Joan Little was led by Black women (many of them gay), from dyke luminaries like Angela Davis and Bernice Johnson Reagon to Karen Galloway, Little’s lawyer, to local Raleigh activists in groups like AFW. Thuma points out that the turnout among white North Carolina feminists on Little’s behalf was generally poor. There were exceptions; white women in majority-white groups like the Triangle Area Lesbian Feminists, the leftist Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and local socialist feminists groups pitched in to help with fundraising and organizing events. The Triangle Area Lesbian Feminists in particular collaborated with the Black-led AFW, with several members joining both groups, and they published missives from NCCCW in their newsletter Feminary. Still, for many local white feminists, ingrained racism and a reticence to fully condemn the criminal justice system stood in the way of offering meaningful support to Little’s campaign. Iterating on Davis’s article in Ms. Magazine, Thuma writes, “Little’s case afforded yet another object lesson in the ‘rape-racism nexus’: when white feminists treat rape as solely an issue of male supremacy and demand a ‘get tough’ response from the police and courts, they will not only fail to stem rape but strengthen a criminal justice system pervaded by racism and class bias—the same system that ensnares and harms women like Little.”6

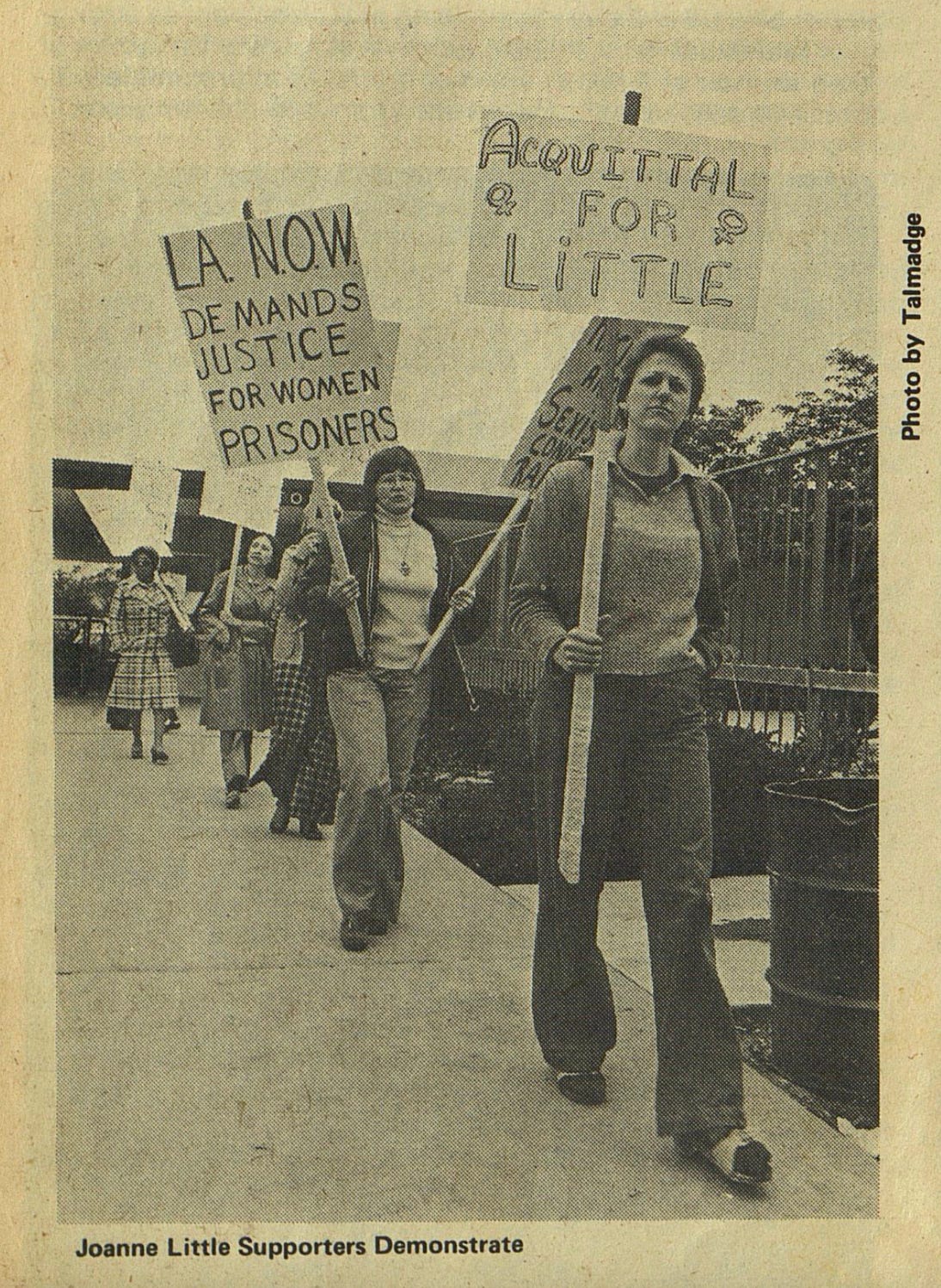

Though local turnout amongst local majority-white feminist groups left much to be desired, the movement to support Joan Little’s case spread around the country, including through lesbian feminist networks. A 1975 issue of the L.A.-based paper The Lesbian Tide featured an article by Jeanne Cordova covering Little’s case, plus a picture taken at an L.A. solidarity protest outside the local women’s county jail. The article linked Little’s case to that of Inez Garcia, a California farm worker who was convicted of second degree murder after shooting her rapist. That same issue featured Saxe on its cover, and an article about "FBI dragnets” in the lesbian community through the use of Grand Juries. Don’t trust the state, resist intimidation, and invest in solidarity - this was the only way forward, the magazine suggested.

This was a moment where you could see a split form between diverging paths in the movement: abolition feminism and carceral feminism. Carceral feminism, if you haven’t encountered this term, is a name used by critics to refer to feminist formations which propose policing and incarceration as solutions to issues facing women. Abolition feminism, a term credited to Davis, Gina Dent, Erica R. Meiners, and Beth E. Richie, refers to feminist politics that advocate for prison abolition. We might think of these as two strands of feminist thought that face off in various historical contexts, often squaring off on issues like rape, sexual violence, sex work, and human trafficking.

In 1975, the same year as Little’s trial, the journalist Susan Brownmiller published her book Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape, which vaulted her to fame. Brownmiller had risen up through radical feminist circles in New York, and her book argued that rape constituted a form of psychological warfare by men against women, which kept women in a state of constant fear. Though widely lauded, Against Our Will was criticized by some feminists, including Davis, for its calls to increase arrests and prison sentences for rapists. In a 1976 pamphlet published by the Sojourner Truth Organization, the writer Alison Edwards wrote, “Never before has the media been so friendly to radical feminism. But then again, never before has radical feminism been so eager to place itself at the forefront of the ‘fight against crime,’ wholeheartedly supporting the basic premises and institutions of our society that underlie all oppression, including that of women.”7 Despite its radical-sounding language, the book was fundamentally a “law and order” book that appealed to liberals. As Edwards pointed out, “like all cries for law and order these days, it is a book with strong racist overtones.”8

As a poor Black woman with a criminal record, Joan Little was not a “perfect victim” in the eyes of some feminists more invested in locking perpetrators up than burning prisons down. Nevertheless, the effort to free Joan Little was broad, well-organized, and successful. Following a five-week-long trial, the jury delivered a not-guilty verdict after deliberating for less than an hour and a half, making Little the first woman in U.S. history to be acquitted of murder for self defense against rape. Little returned to prison to complete her initial sentence for breaking and entering. Iconically, she escaped prison for a second time, though she was then captured and re-sentenced. Little was freed for good in 1979 and moved to New York City. She left the public eye, but as far as I know she is still alive.

Little’s struggle served as a beacon for her incarcerated comrades. After her acquittal, a prisoner at NCCCW wrote, “as the power of the people has freed sister Joann, so shall it free the many brothers and sisters of the dehumanizing conditions and treatment we are currently forced to endure.”9 This is, of course, a vision yet to be realized, but I find so much hope in this woman’s vision of the power to be found in regular people working together: a power greater than wall, chains, or bars.

I’ll continue this series with more dispatches from the history of lesbian and feminist anti-carceral, anti-state, and abolitionist activism. Sending you all strength and peace <3

Emily Thuma, All Our Trials: Prisons, Policing, and the Feminist Fight to End Violence (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2019), 22, 27.

Angela Davis, "Joan Little and The Dialectics of Rape,” Ms. Magazine (June, 1975).

Thuma, 21.

Thuma, 29.

Thuma, 30.

Thuma, 32.

Alison Edwards, “Rape, Racism, and the White Women’s Movement” (Sojourner Truth Organization, 1976), 1.

Edwards, 1.

Thuma, 30.

I always spend Valentine's evening at the vigil and march for missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people. The work its organizers do to keep their love and rage for their friends and family alive means a lot to me, and that they invite anyone who wants to be there into it.

It's a really really strong reminder of how cops and the state and extractive industry works hand in hand to try and destroy Indigenous women. I think it'd be a hard event to attend and come away with any kind of belief that justice or dignity or human thriving can come from a carceral system. I appreciated reading this this morning, after being there last night. I'm glad to hear Joan Little may still be alive, I hope her life is peaceful and happy.

I really appreciated this reminder of how organizers and organizing from history is neither one-dimensional or just a "starting point" to do bigger and better organizing now. In our overstimulating, polycrisis times, we need to channel that kind of clarity.

Do you think the carceral feminists of the 70s map directly onto the modern-day radical feminists (TERFs) of today? As in, these tendencies are fundamentally about "protecting the club" than liberation