Lesbian Interiors, Part 3: The Woman's Building, Los Angeles

A now-vacant bastion of feminist art-making

Hello friends and lovers! I’m blasting into your inbox today with the third installment of my Lesbian Interiors series, highlighting spaces and places that are significant to lesbian feminist history. Today we’ll be visiting the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles, which I visited IRL last month! This will be an image-heavy newsletter, seeing as sick images of the Woman’s Building and its inhabitants abound.

I learned of the Woman’s Building while in LA, visiting Clover’s brother at the start of our road trip. As a very enthusiastic ally, he put together a little tour of historic sites significant to LGBT history across the city. Here are Clover and Jeremy on the Mattachine Steps, which run past the house where Harry Hay and his comrades first founded the Mattachine Society:

The Woman’s Building was one of the stops on our tour. Here’s what it looks like currently, as well as myself in front of it for posterity:

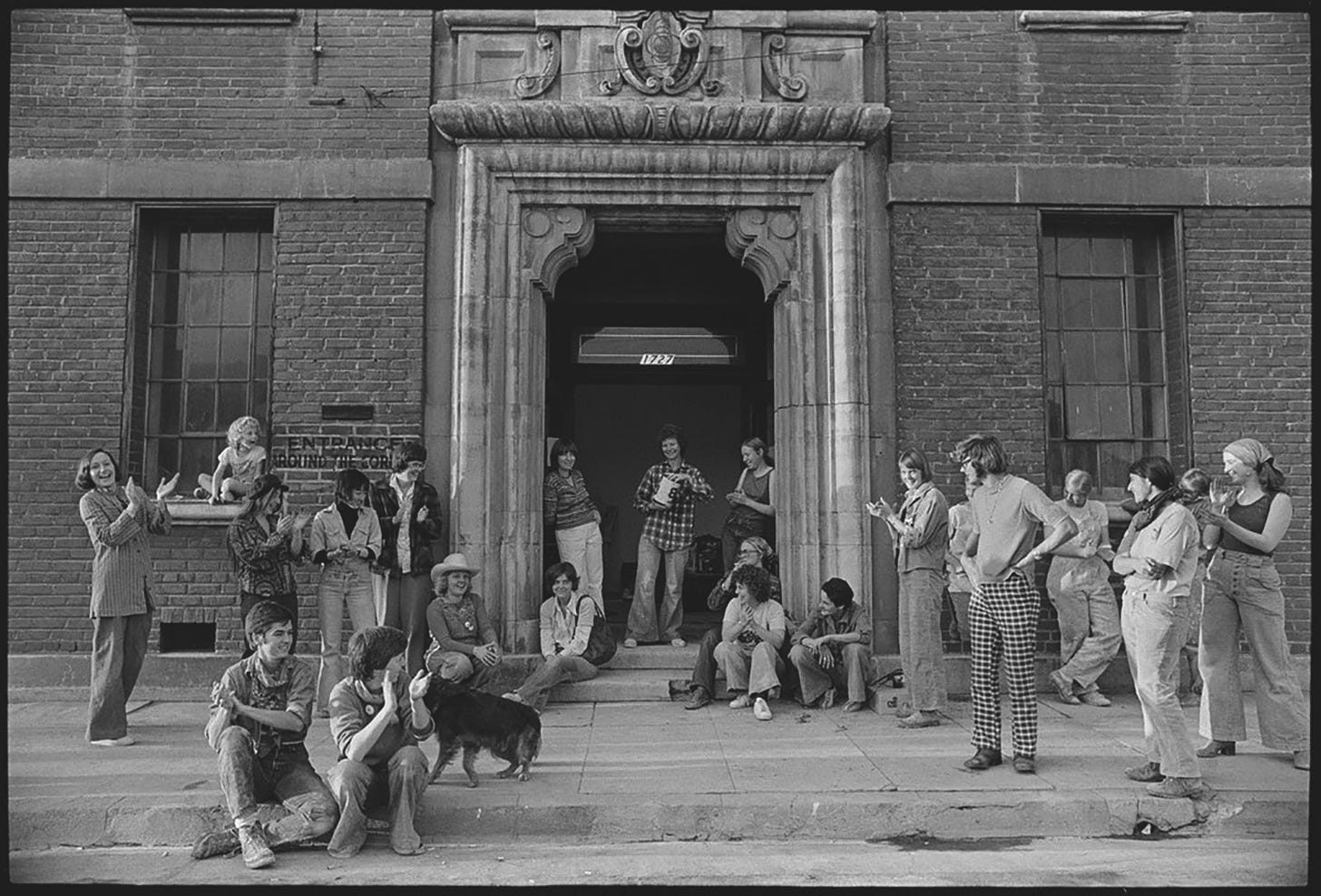

But it once looked like this:

The building was originally built by Standard Oil in the 1914, and was later used as a warehouse. As you can see, it merges beauty and utility: a boxy brick warehouse with beautiful Beaux Arts stonework details. Its life as the Women’s Building began in 1975, when it was rented out by a group of women calling themselves the Feminist Studio Workshop.

The FSW had been founded two years earlier, in 1973, by three CalArts teachers: the artist Judy Chicago (of “The Dinner Party” fame), the graphic designer Sheila de Bretteville, and art historian Arlene Raven. All three were engaged in feminist activism and pedagogy, and sick of toiling away within the patriarchal atmosphere of CalArts and other universities. They quit their jobs and created the FSW, the first independent feminist art schools for women. The FSW was rooted in principles of collaboration, the nurturing of identity and thought as well as artistic skill, and the integration of art and activism. Terry Wolverton, a writer who moved from Michigan to L.A. to work at the Woman’s Building and served as its executive director for a time, recalls that “what was wonderful about [the FSW] was that the different disciplines were not separated, and collaboration was encouraged. It not only encouraged women to focus on their experience as women, it mandated it.”

The group first met in de Bretteville’s home, and then in a building near MacArthur Park, which they named The Woman’s Building after an obscure attraction at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. When that building was sold, the tenants moved into the downtown Beaux Arts warehouse at 1727 North Spring St, and that became the new Woman’s Building. Of course, they had to do some Lesbian Renovations:

The building soon became home to a host of feminist arts organization, women’s gallery spaces, and studios for woman artists. Cheri Gaulke, an artists and longtime board member of the building, recalled that “we never had any traditional administrative structure because we were all artists. We didn’t know how to run a building, and in the ‘70s, the economy was such that you could get away with that. You could float on the strength of a vision.”

Of all the art that came out of the Woman’s Building community, much of the most impactful and innovative work was in the realm of performance art. A performance group called the Waitresses emerged out of the FSW, which explored issues of women’s labor and expected servitude through the archetype of the waitress. Based on this image, their performances were also fucking fun:

Women from the building also put on a 1977 performance called In Mourning and in Rage, staged on the steps of L.A.’s City Hall. Organized by Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz, the performance honored the victims of the “hillside strangler” and protested both violence against women and the sensationalist news coverage that fetishized it. As Lacy writes, “In spite of a growing body of literature on the politics of crimes against women, stories focused instead on the randomness and inevitability of the violence, the life circumstances of the women victims, and the personality characteristics of the anonymous murderer. In Mourning and In Rage was a media performance offering an alternative interpretation of the case that included a feminist analysis of violence.” This interpretation focused instead on how the killings were part of a societal web of violence against women which takes myriad forms. (Worth noting that much of their critique easily maps on to the explosion of true-crime media in recent years!)

Lacy describes the performance thusly: “A motorcade of sixty women followed a hearse to City Hall, where news media reporters waited. Ten very tall women robed in black like 19th century mourners climbed from the hearse. At the front steps of City Hall, the performers each announced a different form of violence against women, connecting these as part of a fabric of social consent. After each of the ten performers spoke, the women from the motorcade, now surrounding the City Hall steps and forming a Greek chorus, yelled “In memory of our sisters, we fight back!” The tenth woman, clothed in red, stepped forward to represent the capacity for self-defense. City Council members voiced support to the press and the Rape Hotline Alliance pledged to start self-defense classes. Singer-songwriter Holly Near created “Fight Back” the night before and sang it a cappella in the City Plaza. The performance reached its target with extensive coverage on local and statewide news.”

The performance artist Barbara T. Smith was also affiliated with the building. Here are her notes for one 1973 performance, titled Feed Me, now archived at the Getty. I love seeing this type of document!

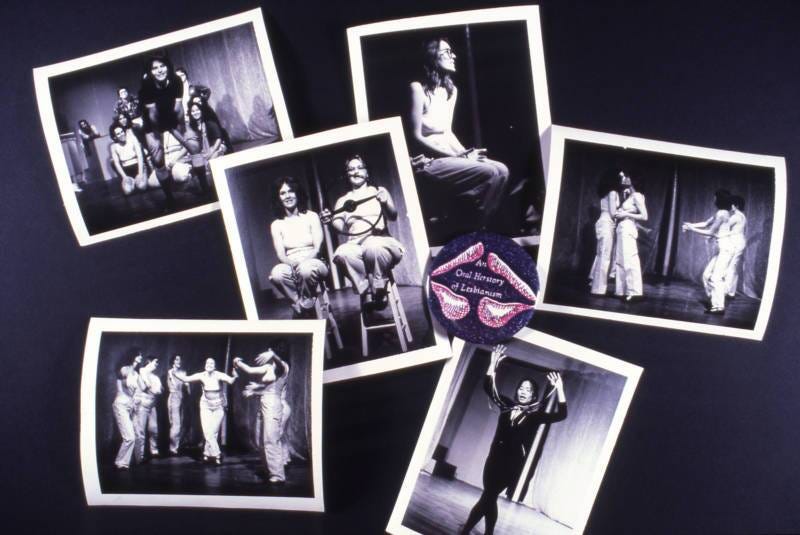

The Woman’s Building was also home to the Lesbian Art Project (LAP), founded by Raven and Terry Wolverton. The group developed writings, performances, and exhibits exploring lesbian culture and foregrounding lesbian contributions to art history. Wolverton created a performance called “An Oral Herstory of Lesbianism,” staged at the Woman’s Building in 1979 by thirteen performers. Here are some images:

As feminist art-making became more accepted and institutionally supported (or entrenched…) within mainstream universities, galleries, and organizations, demand for institutions like the FSW decreased. In 1981, the FSW closed, and far as I can tell, many of the galleries and such within the building also closed around this time. The Woman’s Building held on, primarily as a home for studio rentals for woman artists. The building also supported itself through Women's Graphic Center Typesetting and Design, a for-profit design and printing service. The building struggled throughout the eighties: it was hard to support the rent for such a large building, and the spread-out nature of L.A.’s downtown made foot traffic difficult.

Additionally, as reported in the L.A. Times in 1992, cultural schisms within the feminist movement led to power struggles within the building. “1980 was the great lesbian showdown--whether the Woman’s Building was going to be all lesbian or not,” reported Linda Burnham, a performance art curator. “They began to be seen as an exclusive organization, and funding and public opinion went in a different direction, toward inclusion rather than exclusion for nonprofit arts.” I won’t get too into the weeds of unpacking this particular case, but there’s our old friend separatism, standing at the center of conflicting idealistic and practical concerns! As was common in this era, struggles over separatist visions for feminist spaces proved hard to overcome.

In 1991, the design company shuttered and the Woman’s Building officially closed. Its records were dispersed to the Smithsonian Archives, the Getty Archives, and ONE Archives (an LGBT org). Its legacy was also celebrated in an exhibition in 2011 at the Otis College of Art and Design, titled “Doin It In Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman's Building.”

As far as we could tell when visiting in June, the building now sits empty. It has been marked as a historic site by the L.A. Conservancy, but there was nothing to indicate its history on-site. As we walked the perimeter of the building, we talked about how sad it is that urban economies today have made it so impossibly difficult for shoe-string operations like the Woman’s Building to exist. In cities across the US, access to warehouse spaces has become more difficult. Meanwhile, buildings like this one sit empty, providing no value to the people of the city. The future of the building is unclear. As I wrote about here, I hope that the history of this space and others like it can lead us not toward nostalgia, but toward asking how we, today, can create spaces that allow us to thrive. But fuck do the constraints of capitalism and profiteering real estate ever make it hard.

Sources:

Jan Breslaur, “Woman’s Building Lost to a Hitch in Her-Story”, L.A. Times

Andra Darlington, “Preserving the Legacy of the Los Angeles Woman’s Building, Getty

Laura Dominguez, “The Woman’s Building: L.A.’s ‘Feminist Mecca,’” KCET

Hi. Thanks for this article and for all of your research. I wanted to mention that in the second to last paragraph you say the Woman's Building closed in 1981. It was 1991. Since this is online I am hoping you can easily correct that. Also you might be interested to know that I am in post-production on a feature documentary about the Woman's Building and feminist performance art in 1970s-80s Los Angeles. You can learn more here. https://actinglikewomen.com/ -Cheri Gaulke

This is so cool and needed. The photos, wow. :''')